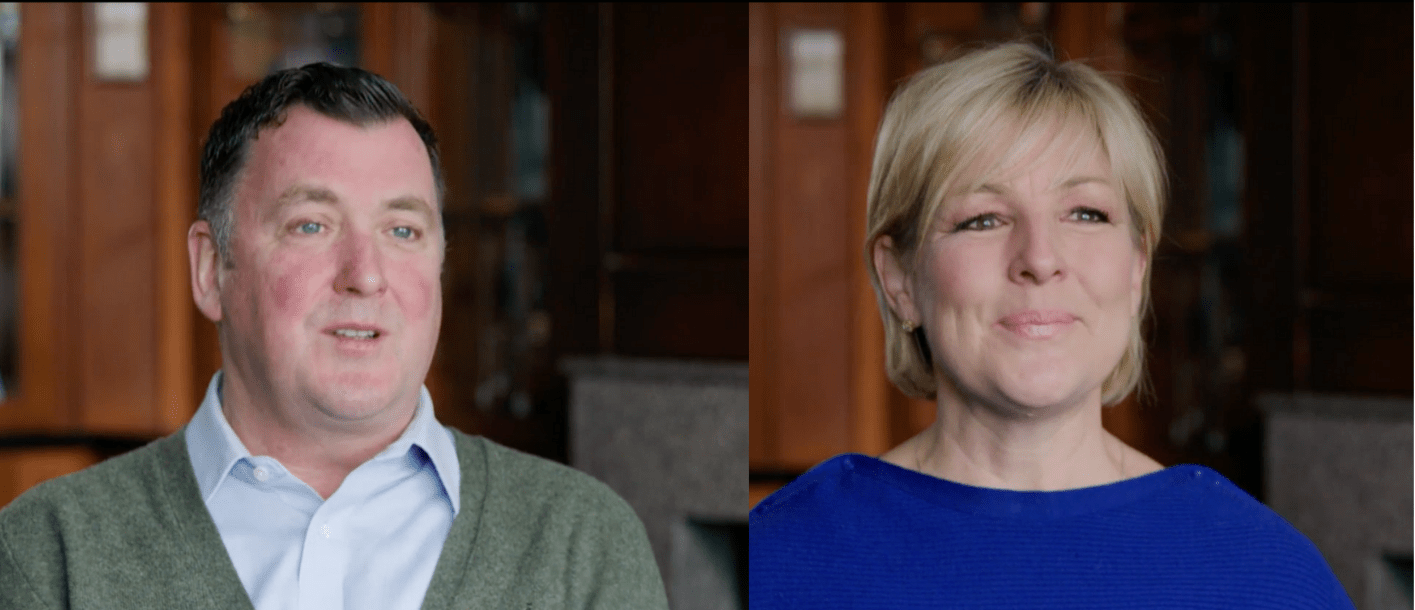

This article is part of Third Factor’s Story Behind the Story series, in which we unpack the stories behind both iconic and under-the-radar Olympic and Paralympic moments. In this feature, Third Factor Partner Sandra Stark shares the mental performance work she and Peter Jensen did with Canadian figure skaters Brian Orser and Tracy Wilson ahead of the 1988 Calgary Winter Olympics to help them manage pressure and perform when the stakes were highest.

—

The 1988 Winter Olympics in Calgary were one of the most pressure-filled environments Canadian athletes had ever faced. Canada had never won an Olympic gold medal on home soil, the expectations were immense, and national attention was relentless. Nowhere was the spotlight brighter than on figure skating.

Brian Orser entered the Games as the reigning world champion and the central figure in what the media called the “Battle of the Brians,” a highly publicized rivalry with American Brian Boitano. He was Canada’s flag bearer and one of the country’s best hopes for gold. Everywhere he went, strangers reminded him what the country expected – “don’t let us down.”

At the same time, ice dancers Tracy Wilson and Rob McCall were carrying a different kind of pressure. Canada had never won an Olympic medal in ice dance, and breaking the long-standing dominance of the Soviet teams was widely viewed as unlikely.

What the public saw was composure under extraordinary pressure. Orser delivered a near-flawless performance to win silver by the narrowest of margins, and Wilson and McCall captured an unexpected bronze, part of a remarkable showing in which figure skaters won three of Canada’s five medals. What most people didn’t see was the internal challenge both athletes were managing.

Whenever something important is on the line and the outcome is uncertain, arousal – the body’s activation level – increases. The heart rate rises. Muscles tighten. Attention narrows. Up to a point, this activation improves performance. But when arousal climbs too high, execution suffers. Timing slips. Decision-making tightens. Small errors multiply.

This is why elite performers don’t just train physically. They train to manage their activation level so they can perform at their best when the pressure is highest. The goal isn’t to eliminate nerves – that isn’t possible when something really matters – but instead to keep arousal within a functional range.

In service of this, two years before the Games, the Canadian Figure Skating Association made mental preparation a priority. They brought in Peter and I to help athletes identify the moments that would elevate their arousal and develop specific plans for managing their arousal when those moments arrive.

Here are two of the techniques that we used, as relayed in conversation with Brian and Tracy.

Lesson #1: Plan for Reality Instead of Avoiding It

After the World Championships in Geneva, where Brian was not happy with how he skated, Peter asked him how he was preparing mentally before skating. Brian explained that he “had all the showers turned on in the dressing room so he wouldn’t hear how the Russian skater [who went ahead of him] had done.”

Standing in the noise of the shower, Brian imagined the Russian had skated brilliantly. In reality, the Russian had fallen on both triple axels. In trying to avoid reality, Brian instead magnified his anxiety.

“That was the turning point,” Peter explains. From then on, Brian’s training approach shifted: instead of trying to shut out uncertainty, Peter worked with Brian to plan for it. Together they laid out exactly what he would do after warm-up: walk through his program, rehearse key jumps, and – most importantly – rehearse the opening segment he was about to skate.

In figure skating competitions, skating order matters – and skaters don’t learn their order to skate until the day before they skate the short program. If you skate late, you may have an agonizing half-hour wait after your warm-up to compete. If you skate early, you may not even leave the ice – which feels incredibly rushed.

Brian hated skating first – but instead of hoping it wouldn’t happen, Peter helped him normalize it by creating a plan for each scenario:

“We developed a routine that worked for me,” Brian explains. “A skating-first routine, a skating-sixth routine. We were prepared for any scenario.” The plan removed the uncertainty and second guessing that could creep in. Once Brian had clarity on what he was going to pay attention to and practised it; he could maintain control over his arousal level. This wasn’t about calming down, it was about restoring control.

In particular, they agreed that if Brian drew his dreaded skating-first slot, he would skate only part of the warm-up, step off the ice, and walk through the opening of his program – physically and mentally – with skate guards on. He would mentally rehearse through to his first major jump, then return to the ice once his warm-up ended.

At the Olympics, that exact scenario played out. Brian skated first in the short program – and won it convincingly. Anyone watching would never have known how uncomfortable that situation was for him.

Listen to Brian talk about the steps that lead to a great performance:

Lesson #2: Train For High Arousal Instead of Trying to Eliminate It

Tracy Wilson knew exactly when her arousal would spike: the moment she stepped onto the ice and heard her name announced in a packed Calgary arena. “Nothing would get me more jazzed up than hearing ‘Tracy Wilson, Rob McCall, Canada,’” she recalls.

Instead of trying to suppress that reaction and stay calm, she trained for it.

Tracy used vivid mental imagery, rehearsed repeatedly in everyday moments: driving to the rink or lying in bed at night. “I hear the announcement and I observe how I feel,” she explains. Then she ran a specific attentional cue: “I hear the noise … I’m going to go under the noise. It’s there. It’s going to go over. It’s going to go behind my back and down.”

This wasn’t intellectual visualization. It was sensory and physical. Because the body responds to imagery as if it’s real, repetition trained her nervous system to respond automatically.

Peter and I saw this pattern repeatedly: performers assume the goal is to eliminate nerves. But when something matters, high arousal is inevitable. The skill is learning to perform with it and keeping it within a functional range by directing attention to where it belongs.

Tracy’s imagery did exactly that. It kept her focus on skating to centre ice, waiting for the music, and entering the opening movements, rather than drifting toward outcomes, judgments, or expectations.

Listen to Tracy discuss training and preparation for emotional moments:

What This Means for You

The more important something is, and the more uncertainty it contains, the higher your activation will rise. The question isn’t whether you’ll feel pressure but rather how you will respond to it.

And how you respond in the moment is a function of how you’ve trained and what you’ve practiced: Orser used structure to manage waiting and uncertainty. Wilson used imagery to regulate the surge that came with public introduction. Different methods, same objective: directing attention toward controllable actions and away from the thoughts and feelings that lead to overwhelm.

Whether you’re stepping onto Olympic ice or into a high-stakes meeting, the principle is the same: you don’t rise to the occasion, you default to what you’ve trained.

Here are four ways to apply the principles of mental preparation to your reality:

- Know your optimal arousal level

When you need to perform – where do you want your energy level to be? A 6 out of 10? An 8 out of 10? In order to manage arousal, you need to have a goal.

- Identify your triggers

What moment will increase your arousal? For Brian it was the wait, for Tracy it was the introduction. Once you identify where you are likely to get thrown off, now you can plan. - Create a strategy

You can use routine like Brian, a mental image like Tracy that directs your focus, or a tool that works best for you to anchor your attention where it will serve you. - Practice it repeatedly

When the moment arrives, your attention will go where it has been trained to go.

Build Resilience In Your Organization

Bring the skills that elite athletes use to build resilience and perform under pressure to your organization. Contact us to learn more about our resilience programs.