This article is part of Third Factor’s Story Behind the Story series, where we look at remarkable Olympic and Paralympic achievements and the athletes who made them happen. This time, we’re featuring Brian and Robin McKeever. Together, they’ve won 16 gold medals in Para Nordic skiing.

—

Brian McKeever is one of Canada’s most accomplished skiers, winning gold at every single winter Paralympics since Salt Lake 2002 (6 in a row), and is now part of the coaching team heading into Milan Cortina. Brian was 19 when he began losing his vision to Stargardt disease. He competed in Para Nordic skiing’s visually impaired category, where athletes ski at full speed but rely on a guide to navigate the course.

That guide was his older brother, Robin. Robin wasn’t a helper on the sidelines – he was an elite skier in his own right. As Brian’s guide, Robin skied directly in front of him during races, setting the pace, choosing lines, calling terrain, and making split-second decisions that affected them both. If Robin made a mistake, Brian paid for it. If Robin wasn’t fast enough, they couldn’t win.

To spectators, the McKeevers’ racing looked effortless: two skiers lined up and moving in sync, linked by trust and quiet communication. What wasn’t visible was how much work it took to build that easy relationship – or how important kindness was to sustaining it.

Brian raced on the same courses and distances as Olympic cross-country skiers. The physical demands were the same. What differed was how results were calculated. In Para Nordic skiing, athletes are classified by disability type, and finishing times are adjusted using a percentage system, like a golf handicap.

For Brian, that system created a unique challenge. Because he was in the least severe vision-loss class, his finishing time was counted at 100 per cent. Athletes with more vision loss had time removed, sometimes significantly. As a result, Brian and Robin often had to win races by minutes to win overall.

Guiding made their reliance on each other unavoidable. In Brian’s category, Robin skied directly in front, choosing the line while Brian drafted behind him. The draft helped – but only if the guide was fast enough to lead. If Brian had to hold back because his guide was not skiing fast enough, there was no way he would win, which meant that Robin had to ski at a level that matched one of Canada’s top able-bodied skiers. As Brian puts it, “I’m not winning without a good guide.”

This wasn’t an individual event with assistance. It was a shared performance.

Kindness Is the Mechanism That Lets Standards Hold

When choosing who to work with, one thing mattered most to the brothers. “Skills can be learned,” Brian says, “but the right compatibility is [most] important.” For Brian and Robin, compatibility meant being able to handle feedback without eroding trust. It wasn’t about being agreeable, it was about keeping standards high while delivering feedback with kindness.

“There could be criticisms, there can be hard conversations,” Brian explains. But when feedback came with “kindness in their hearts and how it’s being presented,” it became “much easier to listen to it and to debrief, and figure out a better way forward.”

That difference mattered for learning. With trust in place, someone could say, “Hey, I think if you do something this way, you’ll be faster,” and it would be heard as help. As Brian says, “we all get better together.”

Robin noticed the same effect. Strong trust meant “less micromanaging.” Standards didn’t drop; roles were clear, intentions were trusted, and learning could continue under pressure.

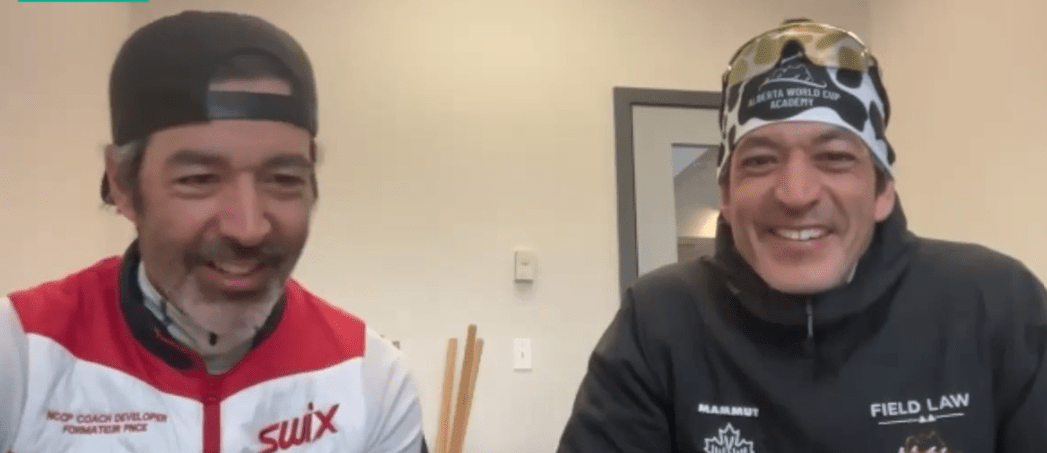

Here’s Brian sharing about the importance of kindness to their culture:

Kindness Can Raise the Bar

One of the most important moments in Brian’s Paralympic career happened because a competitor took the time to help him.

Early in his Para Nordic career, Brian sometimes raced without a guide. In one event, he finished just “30 seconds behind the top guy in the world.” Afterward, the German athlete and his guide told him, “You need to have a guide, because today with a guide, you might have won.”

Brian remembers thinking, “Why would another nation be helping me out on this?” The answer was simple: they were “just excited to have competition.”

That advice changed Brian’s path. Because of that conversation, he asked Robin to guide him, beginning “10 years of pretty fun work racing together.”

Sometimes kindness doesn’t make sport easier. It makes it better.

On why others helped them out to raise the bar:

Trust Is Built in the First Failure, Not the First Success

Their first World Cup together took place at the Salt Lake City Olympic course in March 2001. It was unusually warm – about 15 Celsius, Robin recalls – and the snow was wet and unpredictable. On a fast downhill, something went wrong.

Robin reached the bottom and realized, “Brian’s not there.” He waited, then started hiking back up the course. He heard Brian yelling. What he saw first wasn’t Brian, but “a ski sitting off the edge of the trail.” Brian had caught an edge in the “sloppy snow,” gone off course, and ended up “hanging off of a tree upside down.” Robin climbed down, removed the skis, and pulled him back up.

From Brian’s side, he stepped outside the track to get a push and hit the “mashed potatoes” snow: “My ski stopped and I kept going.” The tree became “the only thing stopping me from sliding headfirst down a steep mud slope.” He held on and waited for Robin. “I figured he’d eventually figure out I wasn’t there,” Brian says.

Robin later called it “a very big failure on day one.” What mattered was what followed. “We laughed about it.” No blame. No anger.

That moment set the tone. Trust wasn’t automatic – even between brothers. It was built through shared experience and protected by how mistakes were handled. Kindness showed up early, not as softness, but as steadiness.

Here’s Robin sharing their early guiding failures:

Autonomy in Preparation. Alignment in Execution.

The McKeevers succeeded because they didn’t pretend they were the same athlete.

As Robin explains, “We have overlapping roles that work together … we have the same end goal, but we still need to arrive there in slightly different ways.” That showed up in training. “We have our own training programs,” he says. “It’s not exactly the same, but we still need to arrive at the same point where we can ski together, race together, and communicate in order to achieve a team victory.”

Brian puts it plainly: “I can ski by myself. Robin can ski by himself, but he’s there to help me. And we are winning this together. We’re not doing this individually.”

Giving each other space reduced friction. Coming together at the right moments kept them aligned. Trust and looking out for each other were the glue that made both possible.

What Leading With Kindness Looks Like in Practice

The McKeevers’ story reveals three practical behaviours that translate directly to leadership and teams:

01.

Reset without blame when something goes wrong.

02.

Deliver feedback as performance support, not personal judgment.

03.

Clarify ownership to reduce micromanagement and create alignment.

01. Reset without blame when something goes wrong

When Brian crashed off the course in Salt Lake City, the response wasn’t panic or finger-pointing. Robin described the day as a failure, but one they laughed about and moved on from. That response preserved trust in a moment where it could have fractured.

02. Deliver feedback as performance support, not personal judgment

Hard conversations were unavoidable, but when framed with respect, people stayed receptive. The feedback that mattered most was specific and performance-focused: if you do this differently, you’ll be faster.

03. Reduce micromanagement by clarifying ownership and alignment

Trust allowed Brian and Robin to prepare in their own way while still arriving at the same execution point. Different paths. Same outcome.

This is kindness without lowering the bar: respect that keeps people engaged, paired with precision that drives improvement.

In the McKeevers’ case, kindness turned trust into medals, and a partnership into a lasting competitive advantage.

—-

Brian will be coaching the Canadian para-Nordic team as they go for gold in Milan-Cortina starting on March 10 (see the team schedule here), while Robin will be supporting the Canadian Nordic team as a member of the coaching staff.

Build Resilience In Your Organization

Bring the skills that elite athletes use to build resilience and perform under pressure to your organization. Contact us to learn more about our resilience programs.