In 2002, the Canadian Women’s National Hockey Team entered the Olympic Games in Salt Lake City in an unfamiliar position: as underdogs. They had not hit their stride as a team, their confidence had taken a hit, and emotions were at risk of boiling over. In eight head-to-head games against the Americans leading up to the Olympics, Canada had lost all eight. For many players, it was hard to avoid memories from four years earlier when the team had lost to the Americans in the gold medal game.

Jayna Hefford, who was playing in the first Games of her Hall of Fame career, recalls the point when the stress and emotion came to a head: “There was an intense conversation in the dressing room with the team. A lot of people had a lot to say about things we needed to do and how we were going to get better, and we realized that a lot of what was happening was the blame game.”

“We realized that a lot of what was happening was the blame game.”

Through a frank, players-only discussion the team was able to come together, but the conversation could have gone a number of different ways. It stayed on track because the team was prepared – mentally and emotionally – to have performance conversations under pressure and surface a number of issues the team needed to resolve. And that preparation turned out to be an important stepping stone to winning gold in Salt Lake City.

Training the bomb squad

Handled poorly, team communication under pressure can lead to combustion. And just like you wouldn’t get success as a bomb disposal technician going in without their toolkit, you won’t find success in communicating through tense situations if your team isn’t prepared. The advantage the women’s team had that allowed them to emerge from that conversation united was a deep awareness of their communication tendencies and systems to counteract the counterproductive ones. They had laid the foundation for performance conversations in good times so that they could happen and be productive when the difficulty hit.

In other words: they had a tool kit and they knew how to use it.

“The biggest opportunity for meaningful growth is often to increase self-awareness and strengthen their ability to communicate productively when under pressure.”

We’ve worked with hundreds of teams in elite sport and business, including the last four medal-winning Canadian women’s hockey teams. One of the things we’ve learned is that when teams are already operating at a high level, the biggest opportunity for meaningful growth is often to increase their self-awareness and strengthen their ability to communicate productively when under pressure. To support this, we’ve developed a process to help teams become more aware of their tendencies, develop systems and practice performance conversations anytime.

At the heart of this process is a tool called the TAIS – The Attentional and Interpersonal Styles inventory. The TAIS was developed for use by Navy SEALs and Olympic athletes, and we’ve found it to be an incredibly valuable tool for diagnosing communication challenges on all kinds of teams. When the pressure is on, when teams are in the midst of setbacks and failure, individuals will fall back on their default communication styles.

Five communication choices

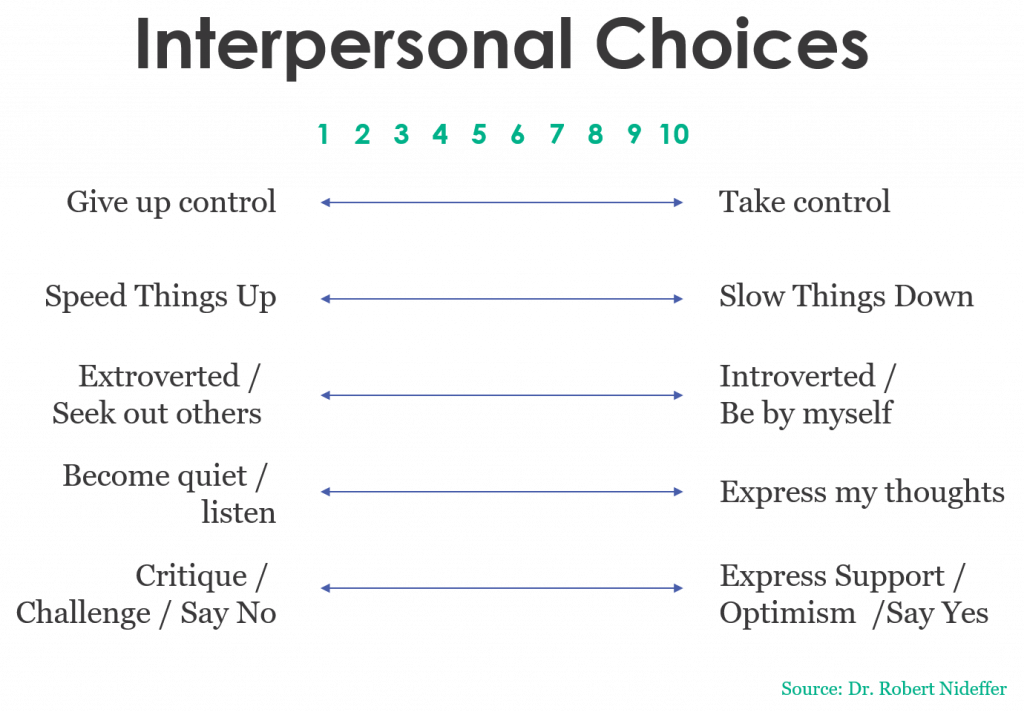

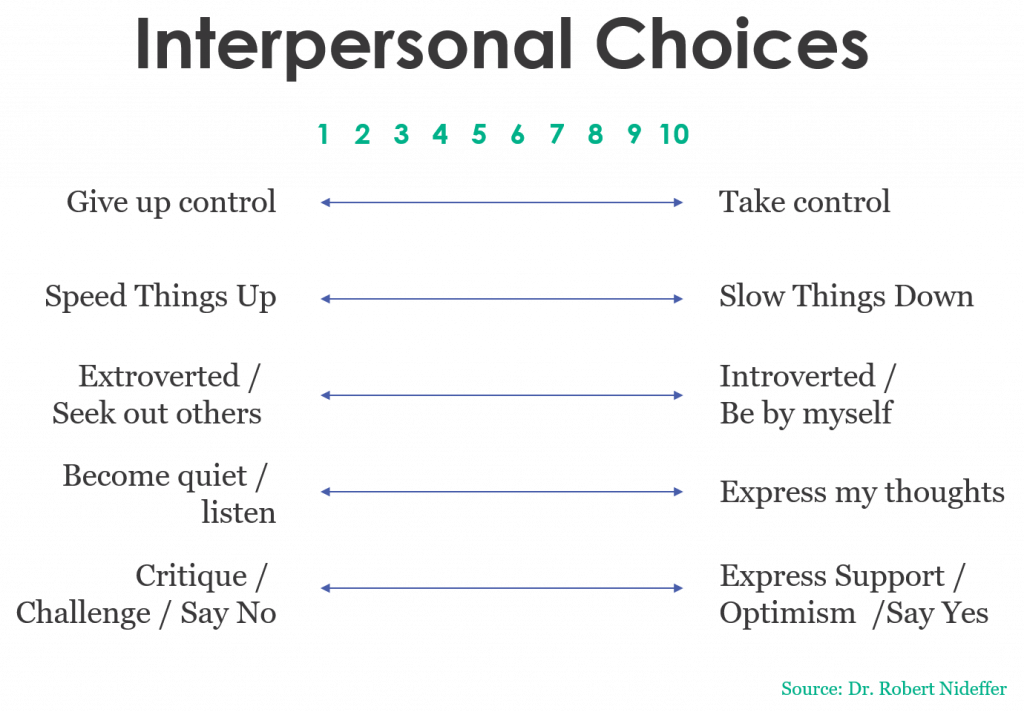

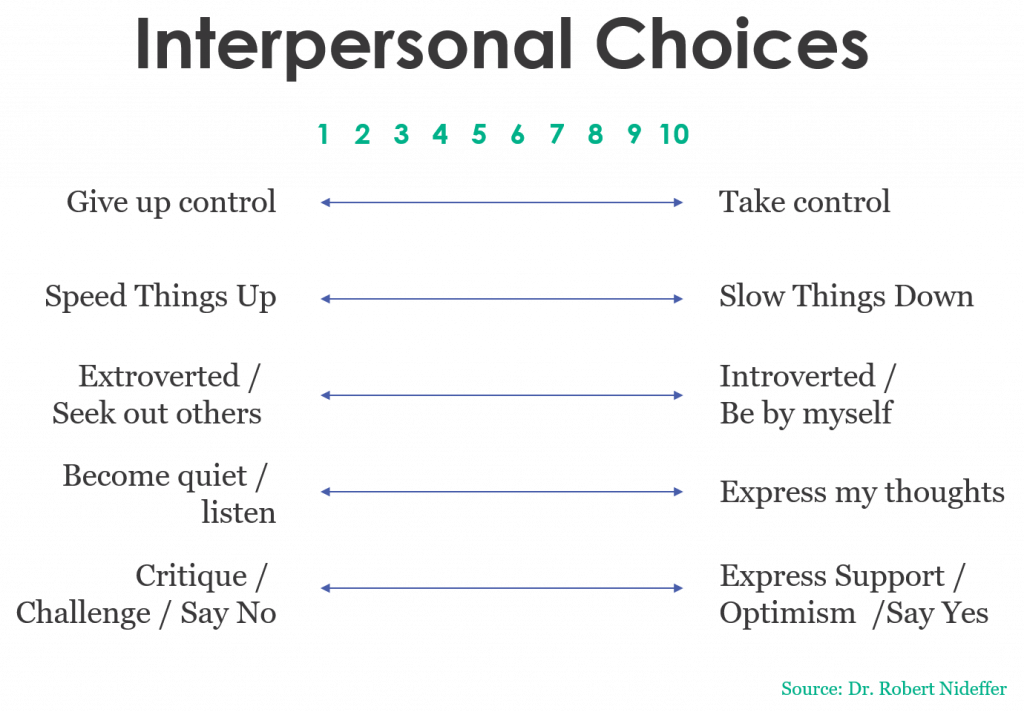

The author of the TAIS, Dr. Robert Nidefer, showed that people make five choices over and over in the course of a conversation. These choices are informed by their tendencies on five dimensions.

Give up/take control – are you more likely to try to take control, or cede control to someone else?

Speed up/slow down – are you more likely to force action or a decision, or encourage more thought and consideration?

Extroverted/introverted – are you going to seek out others, or try to solve the problem yourself?

Become quiet/express thoughts – are you going to become quiet and try to understand, or advocate for your position?

Critique/express support – will you say no and become more critical, or will you say yes and express support?

Cut the right wire

Every team will have members with different tendencies. Ultimately, it’s not the tendencies that matter; it’s the level of awareness team members have of their tendencies, and the systems they put in place to leverage their strengths and weaknesses in the heat of the moment. The highest performing teams we work with take three critical steps in preparing for productive communication under any circumstances.

Acknowledge the “I” in team

Great coaches know that the phrase “there is no I in team” is a myth. Every individual makes their own contribution – and without self-awareness, people can’t adjust. That’s why the first step in your team’s communication action plan is to encourage every individual to build self-awareness across these five choices. By knowing and understanding their default tendencies, team members can begin to recognize their behaviour and course-correct when necessary for the good of the team.

Connect to the “we” of the team

It’s advantageous to know your individual tendencies, and the value is multiplied when that information is shared with everyone on the team. When you raise the waterline of team awareness, everyone can work on the same communication system. Team members can see the intent behind the behaviors their teammates exhibit. The process can be incredibly difficult; Team Canada Captain Hayley Wickenheiser called sharing her profile with her team-mates, “the most stressful part of the 4-year [Olympic] quadrennial.”

Come together as a team

Armed with knowledge of self and others, teams can come together and translate self-awareness into action. When pressure hits, if everybody on the team has the tendency to get louder, express their thoughts and try to take control of the conversation, the team can make decisions in advance to decide who’s going to take control when issues arise. By having these conversations earlier, teams can build systems to fall back on when the pressure is turned up.

Preventing detonation

The next time you’re headed into a potentially high stakes conversations, use the five choices below to carry out a short 3-step preparation exercise:

1. Plot your default tendency on each of the five scales – given your past history, where are you most likely to fall?

2. Where would you ideally like to be as you head into this specific interaction?

3. What are the gaps between your ideal and default style? What actions will you take to ensure you are at your ideal?

Repurpose the fuel for growth

We’ve said before that negative emotion is volatile fuel. Improperly handled, it can lead to combustion. Used properly, it can lead to high performance.

Team communication must go beyond just staying cool during difficult times. Teams must use communication to understand and lean in to their negative emotions, uncover what the emotions are telling them, and frame it as an opportunity for growth. This is what happened with the women’s team in 2002. They prepared to have productive communication at all times, and used the tools they learned to find the opportunity for growth at a moment when it could have blown up. Jayna Hefford explains:

By understanding your individual communication style, sharing your tendencies with the team and proactively planning to address potential faults, your team can find its way through difficult times and not just safely diffuse difficult situations but find new strength and opportunity for higher performance in the process. On November 19th, 2019, 75 leaders from Toronto’s business and HR communities gathered at OCAD U CO for a discussion on team resilience. Here’s what they learned:

Leading the discussion, Third Factor CEO Dane Jensen brought together the voices of elite athletes and coaches to talk about what separates those teams that are able to rebound from failure to reach even higher levels of performance from teams that tend to crumble or falter in the face of failure.

Drawing on insights from our work with high-performing sports teams, including the last four medal winning women’s Olympic hockey teams and the men’s and women’s national soccer teams, Dane identified what it takes for teams to not just perform but also to recover and be resilient. These are the four traits we’ve observed that characterize resilient teams, or differentiate resilient teams from those that are less resilient:

1. Negative emotion. Resilient teams process negative emotion in a way that leads to harder work and higher standards as opposed to detachment or combustion. They frame it so rather than being scared of negative emotion, they choose to lean into it, work with it, and see it with a sense of challenge, control and commitment.

2. Communication. The teams that recover quickly from setbacks communicate differently because they have worked consciously on awareness. They’ve surfaced their communication styles and worked on having performance conversations in the good times.

3. Relationships. Teams are more resilient when they work diligently on building relationships, even if that’s just 30 seconds for each person every day.

4. Shared purpose. Teams work best in the face of failure when they have a clear a line of sight to shared purpose. They don’t do hard work for it’s own sake, but because they choose to connect it to something that actually matters to them.

JOIN US FOR OUR NEXT LEARNING BREAKFAST

Be the first to know about upcoming learning opportunities from Third Factor by entering your information below.

Approximately 1 in 5 Canadians identify as having a disability, and this number will continue to rise as our population ages. At Third Factor, we have a long history of working to reduce barriers for people with disabilities and we want to shine some light on an initiative we’re participating in this week: the annual Rick Hansen Foundation Accessibility Leadership Forum.

Inspired by the belief that anything is possible, Rick Hansen began the Man In Motion World Tour in 1985, wheeling 40,000km over two years. The Rick Hansen Foundation, established in 1988, has made transformational change in raising awareness and removing barriers for people with disabilities, and funding research for the cure and care of people with spinal cord injuries. Today, the Foundation focuses on improving accessibility to create a world that’s accessible and inclusive for all.

In service of this, Rick and the Foundation have brought together a group of leaders from the disability community to collaborate on making Canada the most accessible country in the world. The forum has met annually for the past 4 years to leverage their unique organizational strengths, exchange ideas, build practical recommendations, assess progress, and identify priorities for the coming year.

Since this group first came together we’ve been privileged to work with Rick and his team at the Rick Hansen Foundation to help design the day, making sure that we’re engaging all the stakeholders appropriately and sending them back to the real world with a renewed sense of commitment towards an inclusive and accessible world for people of all abilities.

Third Factor CEO Dane Jensen and Rick Hansen

This year, the focus will be primarily on discussing what it means to be a collaborative community of organizations. How do we think about combining our efforts to make sure that we are punching above our weight and not just acting as a number of independent organizations? We are stronger as a whole and through better corporate collaboration, we can accelerate the pace of progress for people with disabilties.

This year also marks the launch of the Accessibility Professional Network, a membership network created to bring together accessibility professionals, consultants, students and anyone passionate about creating a Canada that’s accessible for all. The network will host its first Annual Accessibility Professional Network Conference on Oct. 31-Nov. 1 in Toronto, which will provide a platform to learn about national and international initiatives in accessibility and contribute to enhancing the field of accessibility in Canada.

Canada is a better place to live because of the important work that Rick and the Foundation have done to raise awareness and remove barriers, and we’re pleased that we’re able to contribute to a movement that’s making a real difference in the lives of people with disabilities in this country.

If you’re interested in doing more to improve accessibility within your organization or community, learn more at the Rick Hansen Foundation.

Sometimes we need to step outside of ourselves in order to better understand what is going on, on the inside.

Self-reflection is one of those things that managers often brush aside. In a forward-focused business environment it can feel as though you just don’t have time to be reflective. However, in order to be great it is crucial to first understand your own strengths and limitations and this understanding rests on the ability to become self-aware.

Sandra Stark and Peggy Baumgartner discuss why self-awareness is important, what it looks like, and the questions you must be able to answer about yourself. They introduce the concept of “active awareness”, a skill that helps you leverage self-awareness in the moment, and that has worked for the thousands of Canadian executives that Third Factor has worked with over the past ten years.

The time that you invest in getting to know yourself in the present, will only serve to benefit you in the future.

Click here to download the whitepaper. “I was covering a colleague’s position while she was on maternity leave. She has now returned and we have negotiated shared authority and management roles. Co-management is not easy. Now we have to see where our roles intersect and what makes us distinct. It was so much easier to be the sole operator and know exactly what my role was and what I was accountable for. I think that is the hardest part. How do we decide about accountability?”

In our workshops, we constantly talk about the importance of clarity. Nowhere is this more important than in areas of joint responsibility. My preferred starting point for clarity in these situations is the basic building block of management responsibility: the decision.

Third Factor CEO Dane Jensen and Rick Hansen

This year, the focus will be primarily on discussing what it means to be a collaborative community of organizations. How do we think about combining our efforts to make sure that we are punching above our weight and not just acting as a number of independent organizations? We are stronger as a whole and through better corporate collaboration, we can accelerate the pace of progress for people with disabilties.

This year also marks the launch of the Accessibility Professional Network, a membership network created to bring together accessibility professionals, consultants, students and anyone passionate about creating a Canada that’s accessible for all. The network will host its first Annual Accessibility Professional Network Conference on Oct. 31-Nov. 1 in Toronto, which will provide a platform to learn about national and international initiatives in accessibility and contribute to enhancing the field of accessibility in Canada.

Canada is a better place to live because of the important work that Rick and the Foundation have done to raise awareness and remove barriers, and we’re pleased that we’re able to contribute to a movement that’s making a real difference in the lives of people with disabilities in this country.

If you’re interested in doing more to improve accessibility within your organization or community, learn more at the Rick Hansen Foundation.

Sometimes we need to step outside of ourselves in order to better understand what is going on, on the inside.

Self-reflection is one of those things that managers often brush aside. In a forward-focused business environment it can feel as though you just don’t have time to be reflective. However, in order to be great it is crucial to first understand your own strengths and limitations and this understanding rests on the ability to become self-aware.

Sandra Stark and Peggy Baumgartner discuss why self-awareness is important, what it looks like, and the questions you must be able to answer about yourself. They introduce the concept of “active awareness”, a skill that helps you leverage self-awareness in the moment, and that has worked for the thousands of Canadian executives that Third Factor has worked with over the past ten years.

The time that you invest in getting to know yourself in the present, will only serve to benefit you in the future.

Click here to download the whitepaper. “I was covering a colleague’s position while she was on maternity leave. She has now returned and we have negotiated shared authority and management roles. Co-management is not easy. Now we have to see where our roles intersect and what makes us distinct. It was so much easier to be the sole operator and know exactly what my role was and what I was accountable for. I think that is the hardest part. How do we decide about accountability?”

In our workshops, we constantly talk about the importance of clarity. Nowhere is this more important than in areas of joint responsibility. My preferred starting point for clarity in these situations is the basic building block of management responsibility: the decision.

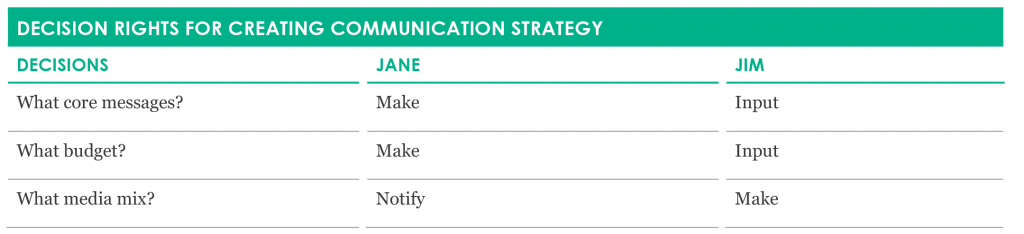

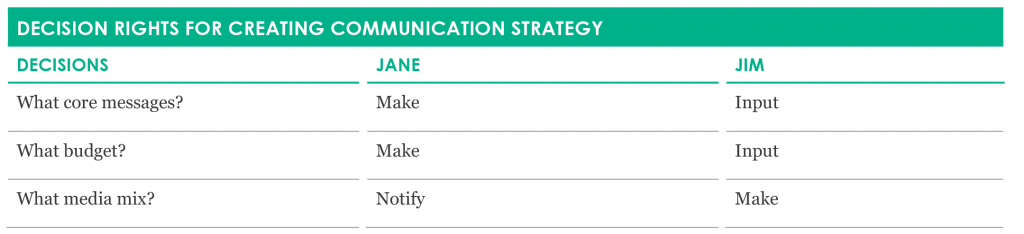

First and foremost, you and your colleague must be on exactly the same page with respect to what the key decisions are that are made in the course of your work, and then you need to have an open and frank discussion around who has the right to ‘make’ the decision vs. who has an ‘input’ right (I.e. They need to be consulted, but ultimately the decision is not theirs to make), or even just a ‘notify’ right (I.e. They must be notified once the decision has been made).

A lot of the issues in shared roles come when people believe they have a make right, but actually they just have an input right, or vice versa. Agreeing on this up front can diffuse a lot of potential tension.

It is very tempting to establish ‘joint make’ rights for key decisions—i.e. we both need to agree to make the decision. In my experience, ‘joint make’ rights cause some significant issues in the real world, and often lead to paralysis. Even though it can be very painful up front, it is better to align on one person who ultimately has the responsibility for making each decision. These ‘make’ rights would ideally be aligned with the unique knowledge, skills, etc. that you bring to the table. Sometimes this may not be possible, but try to use a “joint make” very sparingly.

One way to think about making this real is in going through the core job responsibilities you’ve outlined in your job description and really honing in on what the choices implied in each. For example, let’s say one element of your job is to “oversee the creation and implementation of a comprehensive communication strategy”. Within this task you might have 3 key decisions: 1) what core messages are we highlighting to which audiences, 2) what budget are we allocating for communications, 3) what media mix are we going to use. What you want to do is isolate the decisions that are likely to be hotly contested, and make sure you have clearly laid out decision rights with your partner. For example:

Once decision rights are clarified, accountability is easy: you are accountable to your supervisor for the decisions over which you have a ‘make’ right, and your accountability as colleagues is that you will effectively provide for, and really listen to, input across all decisions where you have agreed that the other person has input rights. Allocating decision rights is an exercise in power. Prepare for the discussion with your colleague to be a challenging one. If you push through it, however, you will have a solid foundation upon which to build a productive, collaborative relationship.

Click here to download this article as a PDF.

Third Factor CEO Dane Jensen and Rick Hansen

This year, the focus will be primarily on discussing what it means to be a collaborative community of organizations. How do we think about combining our efforts to make sure that we are punching above our weight and not just acting as a number of independent organizations? We are stronger as a whole and through better corporate collaboration, we can accelerate the pace of progress for people with disabilties.

This year also marks the launch of the Accessibility Professional Network, a membership network created to bring together accessibility professionals, consultants, students and anyone passionate about creating a Canada that’s accessible for all. The network will host its first Annual Accessibility Professional Network Conference on Oct. 31-Nov. 1 in Toronto, which will provide a platform to learn about national and international initiatives in accessibility and contribute to enhancing the field of accessibility in Canada.

Canada is a better place to live because of the important work that Rick and the Foundation have done to raise awareness and remove barriers, and we’re pleased that we’re able to contribute to a movement that’s making a real difference in the lives of people with disabilities in this country.

If you’re interested in doing more to improve accessibility within your organization or community, learn more at the Rick Hansen Foundation.

Sometimes we need to step outside of ourselves in order to better understand what is going on, on the inside.

Self-reflection is one of those things that managers often brush aside. In a forward-focused business environment it can feel as though you just don’t have time to be reflective. However, in order to be great it is crucial to first understand your own strengths and limitations and this understanding rests on the ability to become self-aware.

Sandra Stark and Peggy Baumgartner discuss why self-awareness is important, what it looks like, and the questions you must be able to answer about yourself. They introduce the concept of “active awareness”, a skill that helps you leverage self-awareness in the moment, and that has worked for the thousands of Canadian executives that Third Factor has worked with over the past ten years.

The time that you invest in getting to know yourself in the present, will only serve to benefit you in the future.

Click here to download the whitepaper. “I was covering a colleague’s position while she was on maternity leave. She has now returned and we have negotiated shared authority and management roles. Co-management is not easy. Now we have to see where our roles intersect and what makes us distinct. It was so much easier to be the sole operator and know exactly what my role was and what I was accountable for. I think that is the hardest part. How do we decide about accountability?”

In our workshops, we constantly talk about the importance of clarity. Nowhere is this more important than in areas of joint responsibility. My preferred starting point for clarity in these situations is the basic building block of management responsibility: the decision.

Third Factor CEO Dane Jensen and Rick Hansen

This year, the focus will be primarily on discussing what it means to be a collaborative community of organizations. How do we think about combining our efforts to make sure that we are punching above our weight and not just acting as a number of independent organizations? We are stronger as a whole and through better corporate collaboration, we can accelerate the pace of progress for people with disabilties.

This year also marks the launch of the Accessibility Professional Network, a membership network created to bring together accessibility professionals, consultants, students and anyone passionate about creating a Canada that’s accessible for all. The network will host its first Annual Accessibility Professional Network Conference on Oct. 31-Nov. 1 in Toronto, which will provide a platform to learn about national and international initiatives in accessibility and contribute to enhancing the field of accessibility in Canada.

Canada is a better place to live because of the important work that Rick and the Foundation have done to raise awareness and remove barriers, and we’re pleased that we’re able to contribute to a movement that’s making a real difference in the lives of people with disabilities in this country.

If you’re interested in doing more to improve accessibility within your organization or community, learn more at the Rick Hansen Foundation.

Sometimes we need to step outside of ourselves in order to better understand what is going on, on the inside.

Self-reflection is one of those things that managers often brush aside. In a forward-focused business environment it can feel as though you just don’t have time to be reflective. However, in order to be great it is crucial to first understand your own strengths and limitations and this understanding rests on the ability to become self-aware.

Sandra Stark and Peggy Baumgartner discuss why self-awareness is important, what it looks like, and the questions you must be able to answer about yourself. They introduce the concept of “active awareness”, a skill that helps you leverage self-awareness in the moment, and that has worked for the thousands of Canadian executives that Third Factor has worked with over the past ten years.

The time that you invest in getting to know yourself in the present, will only serve to benefit you in the future.

Click here to download the whitepaper. “I was covering a colleague’s position while she was on maternity leave. She has now returned and we have negotiated shared authority and management roles. Co-management is not easy. Now we have to see where our roles intersect and what makes us distinct. It was so much easier to be the sole operator and know exactly what my role was and what I was accountable for. I think that is the hardest part. How do we decide about accountability?”

In our workshops, we constantly talk about the importance of clarity. Nowhere is this more important than in areas of joint responsibility. My preferred starting point for clarity in these situations is the basic building block of management responsibility: the decision.