JOIN US FOR OUR NEXT LEARNING BREAKFAST

Be the first to know about upcoming learning opportunities from Third Factor by entering your information below.

“It wasn’t going to define us”Team Captain Christine Sinclair talked about feeling “humiliated” – like they had let down the country. And yet just one year later, the same team outperformed at the London Olympics to win Canada’s first ever medal in soccer. “We knew what we were capable of and just because we had one bad tournament it wasn’t going to define us,” said Sinclair. The head coach of the Women’s National Team, John Herdman, spoke about how the team was “an easy group to motivate” because they had just suffered such a crushing defeat. Negative emotion can be powerful fuel for positive response. It can provide ‘bulletin board material’ that leads to determination, and ultimately harder work and higher standards. But negative emotion is highly volatile fuel. If not handled correctly, it can trigger a negative feedback loop that leads to the blame game and teams that end up either combusting or just detaching.

“As painful as it feels now, it will help him.”So, what does ‘leaning in’ look like? Consider “the shot.” Kawhi Leonard’s quadruple bouncing Game 7 buzzer beater was a moment of euphoria for Toronto. On the other side, however, it was a devastating moment for a young Philadelphia 76ers team featuring 25-year-old star Joel Embiid, who left the court in tears. When asked about the emotional response of Embiid in the post-game press conference, Philadelphia head coach Brett Brown said, “As painful as it feels now, it will help him. It will help shape his career.” Rather than shying away from the pain, comforting Embiid and trying to lessen the sting, Brown leaned into it and helped his young player see it as a growth opportunity – a sign that he needed to work harder. 2. Frame negative emotion differently Leaders of resilient teams have a different answer to the question “what is this pain telling us?” than leaders of less resilient teams. They frame pain as a signal that they aren’t there yet – rather than a sign that they aren’t good enough. As a result of this framing, resilient teams respond to negative emotion with determination. They get committed to the challenges they face by exerting control where it matters: their own effort. After a lacklustre season heading into Salt Lake City in 2002, the Canadian women’s hockey team held a player’s only meeting where they came up with the acronym WAR, for ‘We Are Responsible.’ As 4-time gold medalist Janya Hefford reports, “there was a lot of the blame game going on”– and the WAR framing helped them redirect attention away from the officiating, their opponents, etc. and towards what they were responsible for. Ultimately, this perspective proved vital in overcoming 8 straight penalties in the Gold-Medal game to triumph. 3. Channel negative emotion After embracing negative emotion and finding its meaning, teams and their leaders must still channel the emotion into positive outcomes. Our founder, Peter Jensen, will often ask teams who have suffered failure one powerful question: “What are we going to do with the energy under this emotion?” it’s easy to channel emotion into what Ben Zander has called “the conversation of no possibilities” and allow the dangerous side of negative emotion affect to take over. Channeling negative emotion productively requires individuals on teams to take responsibility for redirecting energy towards growth and hard work.

Be the first to know about upcoming learning opportunities from Third Factor by entering your information below.

Third Factor CEO Dane Jensen and Rick Hansen

This year, the focus will be primarily on discussing what it means to be a collaborative community of organizations. How do we think about combining our efforts to make sure that we are punching above our weight and not just acting as a number of independent organizations? We are stronger as a whole and through better corporate collaboration, we can accelerate the pace of progress for people with disabilties.

This year also marks the launch of the Accessibility Professional Network, a membership network created to bring together accessibility professionals, consultants, students and anyone passionate about creating a Canada that’s accessible for all. The network will host its first Annual Accessibility Professional Network Conference on Oct. 31-Nov. 1 in Toronto, which will provide a platform to learn about national and international initiatives in accessibility and contribute to enhancing the field of accessibility in Canada.

Canada is a better place to live because of the important work that Rick and the Foundation have done to raise awareness and remove barriers, and we’re pleased that we’re able to contribute to a movement that’s making a real difference in the lives of people with disabilities in this country.

If you’re interested in doing more to improve accessibility within your organization or community, learn more at the Rick Hansen Foundation.

Valuing lessons from failure is an important mindset in business, but in reality most teams aren’t prepared to fail. The consequences of failure can breed negativity and erode team culture, destroying productivity, preventing future success, and masking the very lessons that make failure valuable in the first place.

In our 25 years of experience working with hundreds of teams in the worlds of elite sport, business, not-for-profit, Government and Academia – including the last 4 medal-winning Canadian Women’s Olympic hockey teams – we’ve observed the characteristics that define resilient teams, and the steps they and their leaders take to use failure as a catalyst for growth and high performance.

In this keynote address, Third Factor CEO, Dane Jensen, will draw on the lessons we’ve learned from the Olympic athletes we’ve worked with to inspire you with new ideas to foster resilience on teams in your organization by examining four characteristics of resilient teams.

The presentation features the voices of athletes and coaches who have persevered in the face of failure and tremendous pressure, including:

Third Factor CEO Dane Jensen and Rick Hansen

This year, the focus will be primarily on discussing what it means to be a collaborative community of organizations. How do we think about combining our efforts to make sure that we are punching above our weight and not just acting as a number of independent organizations? We are stronger as a whole and through better corporate collaboration, we can accelerate the pace of progress for people with disabilties.

This year also marks the launch of the Accessibility Professional Network, a membership network created to bring together accessibility professionals, consultants, students and anyone passionate about creating a Canada that’s accessible for all. The network will host its first Annual Accessibility Professional Network Conference on Oct. 31-Nov. 1 in Toronto, which will provide a platform to learn about national and international initiatives in accessibility and contribute to enhancing the field of accessibility in Canada.

Canada is a better place to live because of the important work that Rick and the Foundation have done to raise awareness and remove barriers, and we’re pleased that we’re able to contribute to a movement that’s making a real difference in the lives of people with disabilities in this country.

If you’re interested in doing more to improve accessibility within your organization or community, learn more at the Rick Hansen Foundation.

Valuing lessons from failure is an important mindset in business, but in reality most teams aren’t prepared to fail. The consequences of failure can breed negativity and erode team culture, destroying productivity, preventing future success, and masking the very lessons that make failure valuable in the first place.

In our 25 years of experience working with hundreds of teams in the worlds of elite sport, business, not-for-profit, Government and Academia – including the last 4 medal-winning Canadian Women’s Olympic hockey teams – we’ve observed the characteristics that define resilient teams, and the steps they and their leaders take to use failure as a catalyst for growth and high performance.

In this keynote address, Third Factor CEO, Dane Jensen, will draw on the lessons we’ve learned from the Olympic athletes we’ve worked with to inspire you with new ideas to foster resilience on teams in your organization by examining four characteristics of resilient teams.

The presentation features the voices of athletes and coaches who have persevered in the face of failure and tremendous pressure, including:

Dane Jensen is a cross-pollinator between the podium and the boardroom. As CEO of Third Factor, he works every day to enhance Canada’s business and athletic competitiveness through better strategy and stronger leadership. His clients include RBC, CIBC, WestJet, University Health Network, the Canadian Paralympic Committee, the Canadian Sport Institute Ontario, and Right To Play. He has worked as an advisor to Senior Executives in 12 countries on 5 continents, he contributes regularly to The Globe and Mail on the topics of strategy and leadership, and was previously an Associate Partner at the strategy consultancy Monitor Deloitte.

Dane Jensen is a cross-pollinator between the podium and the boardroom. As CEO of Third Factor, he works every day to enhance Canada’s business and athletic competitiveness through better strategy and stronger leadership. His clients include RBC, CIBC, WestJet, University Health Network, the Canadian Paralympic Committee, the Canadian Sport Institute Ontario, and Right To Play. He has worked as an advisor to Senior Executives in 12 countries on 5 continents, he contributes regularly to The Globe and Mail on the topics of strategy and leadership, and was previously an Associate Partner at the strategy consultancy Monitor Deloitte.

Just minutes from Union Station on Toronto’s waterfront, OCAD U CO is a state-of-the-art 14,000 square foot studio designed specifically for collaborative innovation work. The space features is home to 20 resident design-led startups, a suite of formal and informal meeting spaces, and is the setting for our program, How To Lead Innovation, which we run in partnership with OCAD U CO and the Smith School of Business at Queen’s University.

Just minutes from Union Station on Toronto’s waterfront, OCAD U CO is a state-of-the-art 14,000 square foot studio designed specifically for collaborative innovation work. The space features is home to 20 resident design-led startups, a suite of formal and informal meeting spaces, and is the setting for our program, How To Lead Innovation, which we run in partnership with OCAD U CO and the Smith School of Business at Queen’s University.

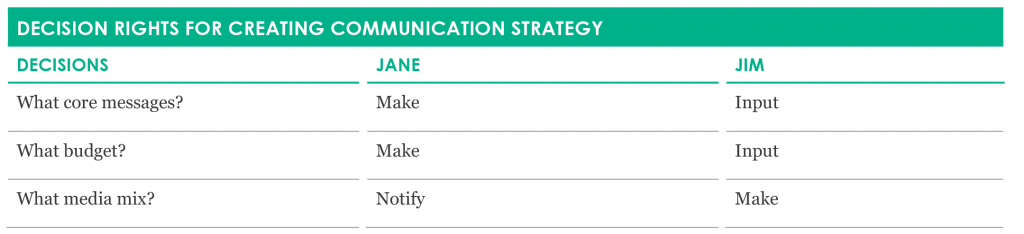

First and foremost, you and your colleague must be on exactly the same page with respect to what the key decisions are that are made in the course of your work, and then you need to have an open and frank discussion around who has the right to ‘make’ the decision vs. who has an ‘input’ right (I.e. They need to be consulted, but ultimately the decision is not theirs to make), or even just a ‘notify’ right (I.e. They must be notified once the decision has been made).

A lot of the issues in shared roles come when people believe they have a make right, but actually they just have an input right, or vice versa. Agreeing on this up front can diffuse a lot of potential tension.

It is very tempting to establish ‘joint make’ rights for key decisions—i.e. we both need to agree to make the decision. In my experience, ‘joint make’ rights cause some significant issues in the real world, and often lead to paralysis. Even though it can be very painful up front, it is better to align on one person who ultimately has the responsibility for making each decision. These ‘make’ rights would ideally be aligned with the unique knowledge, skills, etc. that you bring to the table. Sometimes this may not be possible, but try to use a “joint make” very sparingly.

One way to think about making this real is in going through the core job responsibilities you’ve outlined in your job description and really honing in on what the choices implied in each. For example, let’s say one element of your job is to “oversee the creation and implementation of a comprehensive communication strategy”. Within this task you might have 3 key decisions: 1) what core messages are we highlighting to which audiences, 2) what budget are we allocating for communications, 3) what media mix are we going to use. What you want to do is isolate the decisions that are likely to be hotly contested, and make sure you have clearly laid out decision rights with your partner. For example:

Once decision rights are clarified, accountability is easy: you are accountable to your supervisor for the decisions over which you have a ‘make’ right, and your accountability as colleagues is that you will effectively provide for, and really listen to, input across all decisions where you have agreed that the other person has input rights. Allocating decision rights is an exercise in power. Prepare for the discussion with your colleague to be a challenging one. If you push through it, however, you will have a solid foundation upon which to build a productive, collaborative relationship.