Changing a Canadian mindset

Prior to the Vancouver Olympics, Canada was known in Olympic circles for one notable achievement: it was the only nation in the world to host the Games without a local athlete winning gold. In fact, Canada had achieved this feat twice; first at the 1976 Summer Games in Montreal, and again at the 1988 Winter Games in Calgary. When Vancouver won the bid to host the 2010 Winter Games, Canada’s 13 winter national sport organizations were determined to change that reputation. A report by sport management consultant and Olympic Hall of Famer, Cathy Priestner Allinger, found that Canadian athletes ranked top-five in the world the year before the games were far less likely to go on to win an Olympic medal than international athletes who were performing at the same level.“Canada’s challenge wasn’t producing world-class athletes; it was producing world-class athletes who could perform with all the distractions and pressure of the Olympics”In other words, Canada’s challenge wasn’t producing world-class athletes; it was producing world-class athletes who could perform with all the distractions and pressure of the Olympics. Brian Orser was one of Canada’s star athletes at the Calgary Games in 1988, and he spoke to us about the pressure of competing in front of a home crowd. To help Canada’s performers prepare for the pressure of Olympic competition, the not-for-profit organization Own the Podium was formed to provide and fund support structures designed to give Canadian athletes the preparation that would allow them to access their best performances in the face of Olympic pressure. Own The Podium was a spectacular success. At Vancouver, Canadian athletes won 26 medals, including a record-setting 14 gold medals, placing Canada third overall. Since that time, Canadian athletes have been ‘converting’ at a rate of around 70% and Canadians now enter Olympic Games with an expectation that they could indeed, be the best in the world.

The impact of self-awareness and communication strategies

We had always believed that self-awareness was a critical component of team performance, and there was no doubt on the subject following our work with the Canadian Women’s Olympic Hockey Team at the Vancouver Games. In 2010, the team was looking to defend its gold medal from the Turin Games four years prior. They were also preparing to face their American arch-rivals who had bested them at the world championship the year before. As the team’s mental performance coach, Third Factor Founder, Dr. Peter Jensen, was tasked with helping the team perform through the high-stakes tournament while under intense scrutiny from the home crowd. To help keep the team running like a finely tuned engine, he elected to bring in our collaboration guru, Peggy Baumgartner, to guide the team through our Self-Aware Team process. Through the program, the team was able to gain a better understanding of their tendencies – both individually and as a team under pressure. And, they leveraged that new understanding to design systems to keep communication flowing effectively when the pressure mounted. The players remember it as a challenge that was both extremely difficult, and extremely worthwhile. With a strategy in place, the team was able to communicate and stay consistent whether things were going well or poorly. They were able to work their way through the ups and downs of Olympic competition and successfully defend their gold medal on home ice. What we learned is that when you have a high functioning team – even one that’s among the best in the world – one of the most powerful ways to further enhance their performance is to increase their self-awareness and communication skills.The convergence of health and performance

For us at Third Factor, there was a hidden storyline we were following that was far more significant than the Olympics. One week prior to the start of the Games, Peter Jensen was with the Women’s Olympic Hockey Team in Jasper, Alberta, at their pre-Olympic camp when he received confirmation that he had throat and neck cancer.“Peter had to keep the information from the team so as not to become an enormous distraction”Peter had to notify the leadership at Hockey Canada and, with their blessing, continued to support the mental performance of the Women’s Olympic Hockey Team. As they headed into their most important competition of the four-year cycle, Peter had to keep the information from the team so as not to become an enormous distraction while simultaneously teaching skills, being at his best and dispensing regular doses of his usual sense of humour. Peter is currently cancer-free and maintains a crazy busy schedule delivering keynote speeches to audiences big and small around the world. Peter wrote about his experience in his own words in his whitepaper, When Health and Performance Converge: What I (re)Learned From Cancer. It’s a great read if you’re curious to learn more about how he was able to stay resilient through such a difficult time. To those of us at Third Factor, the 2010 Vancouver Games are a reminder that Peter doesn’t just teach people how to handle pressure, he lives and breathes the content. In 2002, the Canadian Women’s National Hockey Team entered the Olympic Games in Salt Lake City in an unfamiliar position: as underdogs. They had not hit their stride as a team, their confidence had taken a hit, and emotions were at risk of boiling over. In eight head-to-head games against the Americans leading up to the Olympics, Canada had lost all eight. For many players, it was hard to avoid memories from four years earlier when the team had lost to the Americans in the gold medal game. Jayna Hefford, who was playing in the first Games of her Hall of Fame career, recalls the point when the stress and emotion came to a head: “There was an intense conversation in the dressing room with the team. A lot of people had a lot to say about things we needed to do and how we were going to get better, and we realized that a lot of what was happening was the blame game.”

“We realized that a lot of what was happening was the blame game.”Through a frank, players-only discussion the team was able to come together, but the conversation could have gone a number of different ways. It stayed on track because the team was prepared – mentally and emotionally – to have performance conversations under pressure and surface a number of issues the team needed to resolve. And that preparation turned out to be an important stepping stone to winning gold in Salt Lake City.

Training the bomb squad

Handled poorly, team communication under pressure can lead to combustion. And just like you wouldn’t get success as a bomb disposal technician going in without their toolkit, you won’t find success in communicating through tense situations if your team isn’t prepared. The advantage the women’s team had that allowed them to emerge from that conversation united was a deep awareness of their communication tendencies and systems to counteract the counterproductive ones. They had laid the foundation for performance conversations in good times so that they could happen and be productive when the difficulty hit. In other words: they had a tool kit and they knew how to use it.“The biggest opportunity for meaningful growth is often to increase self-awareness and strengthen their ability to communicate productively when under pressure.”We’ve worked with hundreds of teams in elite sport and business, including the last four medal-winning Canadian women’s hockey teams. One of the things we’ve learned is that when teams are already operating at a high level, the biggest opportunity for meaningful growth is often to increase their self-awareness and strengthen their ability to communicate productively when under pressure. To support this, we’ve developed a process to help teams become more aware of their tendencies, develop systems and practice performance conversations anytime. At the heart of this process is a tool called the TAIS – The Attentional and Interpersonal Styles inventory. The TAIS was developed for use by Navy SEALs and Olympic athletes, and we’ve found it to be an incredibly valuable tool for diagnosing communication challenges on all kinds of teams. When the pressure is on, when teams are in the midst of setbacks and failure, individuals will fall back on their default communication styles.

Five communication choices

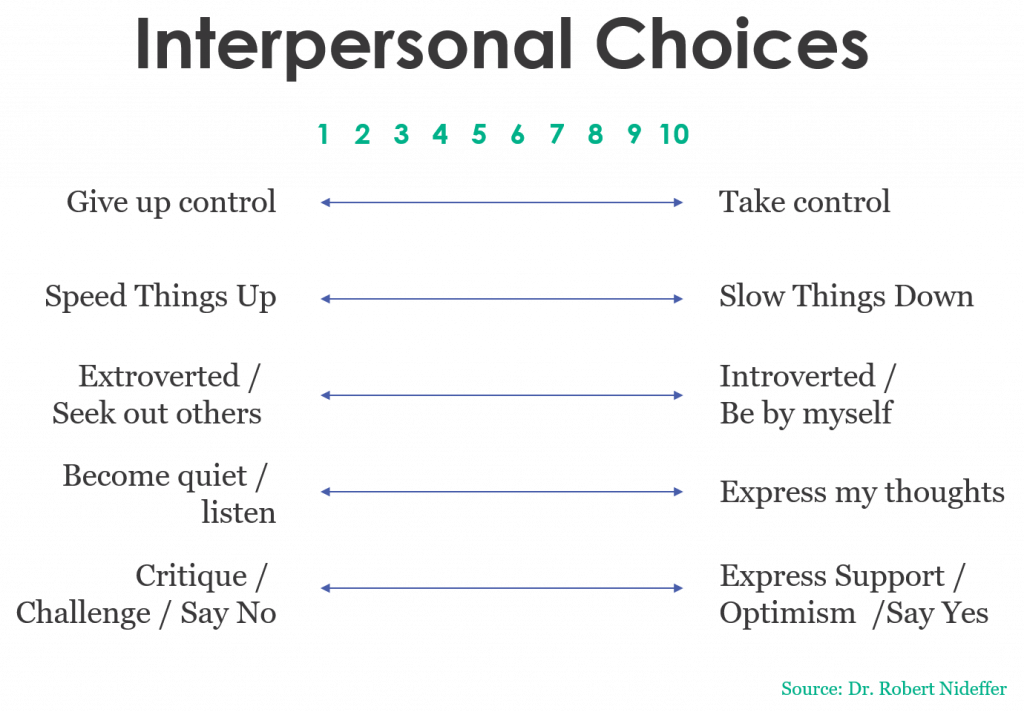

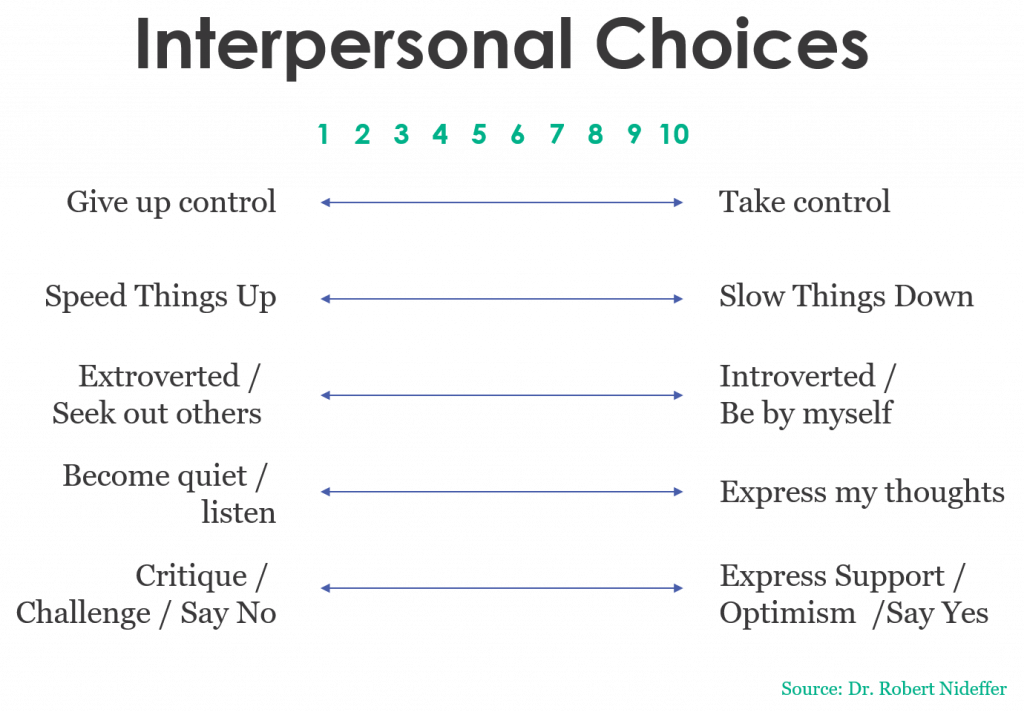

The author of the TAIS, Dr. Robert Nidefer, showed that people make five choices over and over in the course of a conversation. These choices are informed by their tendencies on five dimensions.

Cut the right wire

Every team will have members with different tendencies. Ultimately, it’s not the tendencies that matter; it’s the level of awareness team members have of their tendencies, and the systems they put in place to leverage their strengths and weaknesses in the heat of the moment. The highest performing teams we work with take three critical steps in preparing for productive communication under any circumstances.Acknowledge the “I” in team

Great coaches know that the phrase “there is no I in team” is a myth. Every individual makes their own contribution – and without self-awareness, people can’t adjust. That’s why the first step in your team’s communication action plan is to encourage every individual to build self-awareness across these five choices. By knowing and understanding their default tendencies, team members can begin to recognize their behaviour and course-correct when necessary for the good of the team.Connect to the “we” of the team

It’s advantageous to know your individual tendencies, and the value is multiplied when that information is shared with everyone on the team. When you raise the waterline of team awareness, everyone can work on the same communication system. Team members can see the intent behind the behaviors their teammates exhibit. The process can be incredibly difficult; Team Canada Captain Hayley Wickenheiser called sharing her profile with her team-mates, “the most stressful part of the 4-year [Olympic] quadrennial.”Come together as a team

Armed with knowledge of self and others, teams can come together and translate self-awareness into action. When pressure hits, if everybody on the team has the tendency to get louder, express their thoughts and try to take control of the conversation, the team can make decisions in advance to decide who’s going to take control when issues arise. By having these conversations earlier, teams can build systems to fall back on when the pressure is turned up.Preventing detonation

The next time you’re headed into a potentially high stakes conversations, use the five choices below to carry out a short 3-step preparation exercise:

1. Plot your default tendency on each of the five scales – given your past history, where are you most likely to fall?

2. Where would you ideally like to be as you head into this specific interaction?

3. What are the gaps between your ideal and default style? What actions will you take to ensure you are at your ideal?