Confronting is a Coaching Conversation

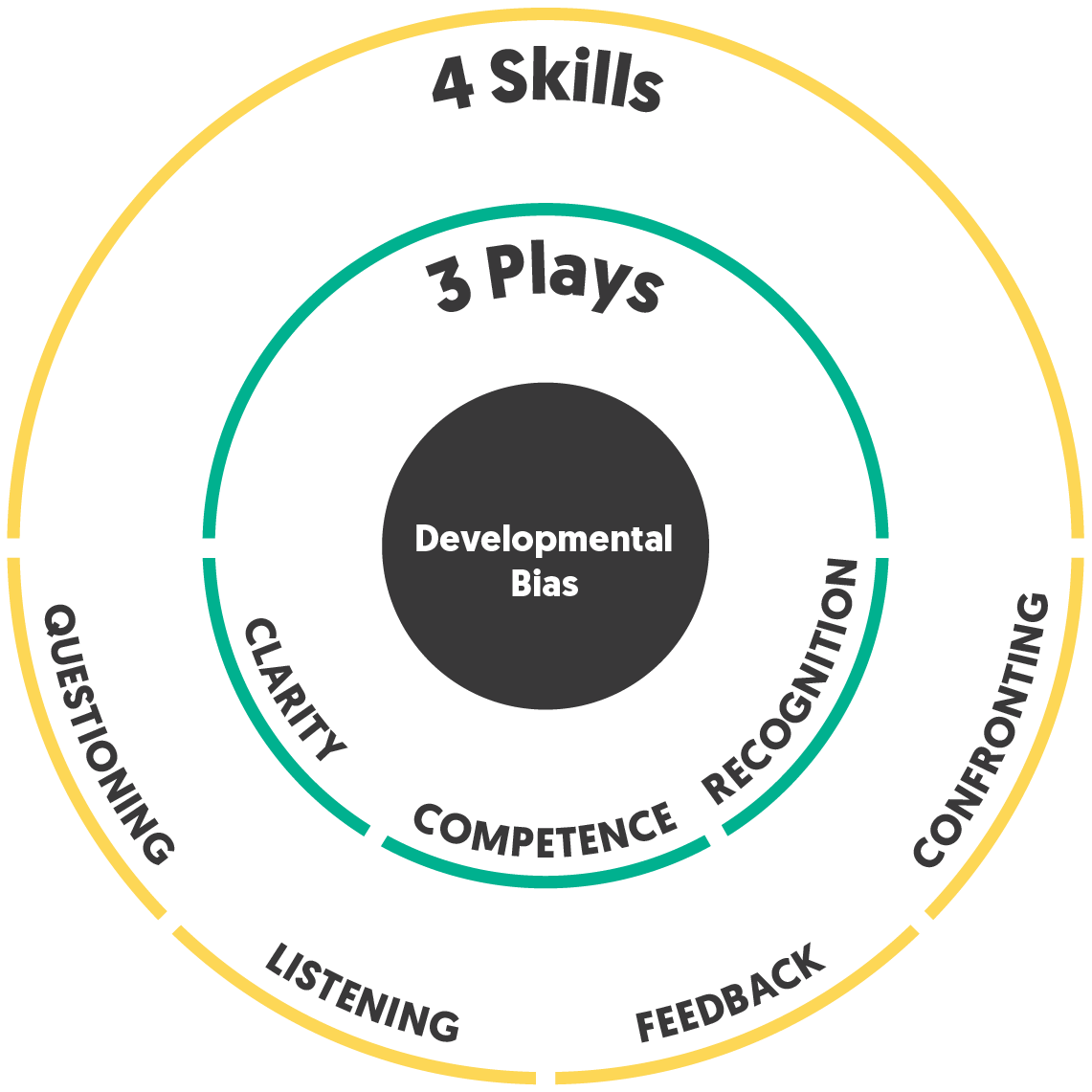

Confronting is a coaching conversation. It doesn’t fit neatly with the popular notion that coaching is just about asking good questions, but watching Olympic coaches operate, as we have for 30 years, makes one thing very clear: having the courage to have a direct conversation when needed is vital to helping someone reach their highest potential. In fact, avoiding a difficult conversation about something that’s preventing a person’s success is the opposite of good coaching. That’s why confronting is one of the four core communication skills in our 3×4 Coaching model, and one that builds on the other three communication skills – questioning, listening, and feedback. It’s not the first or most frequent approach that coaches reach for, but it’s an important part of the overall coaching skill set. Knowing that you can navigate complex, high-stakes conversations is part of what underpins your confidence as a leader.

Choose Your Challenge

Having a confronting conversation with Leo is going to be challenging because I don’t want to damage our relationship. It doesn’t take tremendous courage to call up the airline after my flight was delayed and demand a refund because I only care about getting compensated, not my relationship with the customer service representative. But Leo is one of the strongest performers on my team and I want to have a good relationship after this conversation. It’s also going to be challenging because Leo has been resisting making this change and now it’s getting in the way of his success. This isn’t just a straightforward piece of feedback anymore. There are real stakes. If Leo’s behaviour continues, we could end up in the realm of more formal performance management channels.“When done effectively, these conversations can resolve the issue at hand, build the other person’s commitment to making progress, and strengthen the relationship.”It’s easy to see the threats in these conversations but there are also potential benefits. When done effectively, these conversations can resolve the issue at hand, build the other person’s commitment to making progress, and strengthen the relationship if they see you as someone who holds them to a high standard yet cares about them and respects them. So, I choose my challenge: I can avoid the conversation and deal with the fallout – Leo’s behaviour continues, our relationship becomes strained as my frustration seeps out, and I lose credibility with other people who see me allowing this behaviour to continue. Or I can face the discomfort of addressing the issue head-on and put my coaching skills to the test.

Connection Before Correction

Once I decide to address the issue, how do I have this conversation in a way that not only protects our relationship but gets Leo committed to making a change? It starts before I even enter the conversation. Often, we fall into the trap of thinking that we need to emotionally distance ourselves from the other person in order to be “tough” or objective. But it’s our relationship with the other person that’s the foundation for coaching them. I cannot coach Leo if I lose my connection to him. So rather than distancing myself, I start by strengthening my connection to Leo. I put myself in his shoes and explore the most generous, plausible story I can come up with for why he might be acting this way. Maybe he’s under a lot of pressure that is leaving him with little patience. Maybe I’m not aware of some underlying tension with his teammates. Or maybe Leo is so enthusiastic about his ideas that he doesn’t realize he’s shutting down other people. I choose the story that most strengthens my connection to Leo because it puts me in a mindset to engage in this conversation in a direct but caring way. I also need to get clear on the specific change I want to see – not all the ripple effects of Leo’s dismissive behaviour, or the fact that I’m also irritated because he was late for our team meeting yesterday – but the specific gap between what I need to see from him and what I’m currently getting.Open Strong

Next, I need to prepare my opening statement. This will set the tone and direction for the conversation. Without carefully crafting and practicing my opening, things can go sideways quickly. I could fall into the trap of starting with a sneak attack, “Well Leo, I guess you know why we’re having this conversation…” Or I might unleash my pent-up frustration and anger, leaving Leo like a deer in the headlights trying to respond. Or I might revert to the classic “feedback sandwich”, muddying my message and leaving Leo guessing at what I really mean. An effective opening is short – less than 60 seconds – and clearly articulates the specific behaviour that needs to change, the impact of that behaviour, what’s at stake if it doesn’t change, and my desire to work together to reach a resolution. “Leo, I want to talk to you about a pattern of dismissing input from your peers. For example, in yesterday’s meeting, Sarah raised a concern about the project timeline. You interrupted and said, ‘That’s not really an issue.’ I felt worried that you dismissed her question because I’ve noticed people hesitating to speak up in front of you. This can affect your ability to get the information needed to make good decisions and manage the concerns of staff. Advancing in this organization depends on your ability to build relationships and collaborate effectively. I haven’t been entirely clear on the importance of this, and that’s on me. I want to find a way to modify this behaviour. What are your thoughts?”Drop Your Agenda

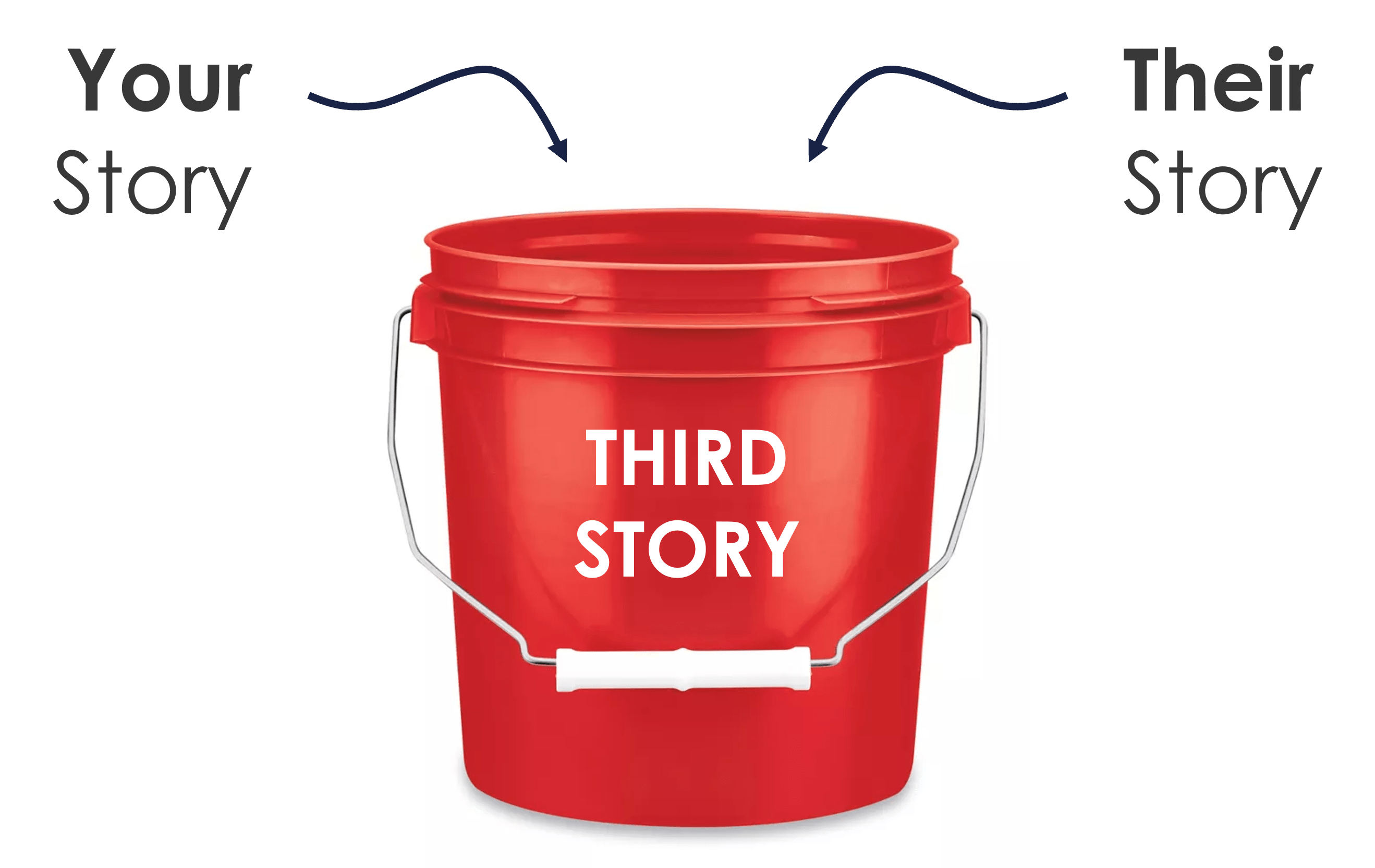

After delivering my opening, it would be great if Leo said, “got it boss, no problem.” But that’s not what typically happens. I’m likely to get resistance – anger, excuses, deflection, or awkward silence. Counter-intuitively, that resistance is not something to fight against or try to “objection handle”; instead, I need to recognize that the path to a solution is through the resistance. So instead of defending my position, I drop my agenda and lean in to explore the resistance I’m getting from Leo. Questioning and listening are the critical coaching skills at this stage of the conversation. Questions to deepen and clarify my understanding of his story: Can you say more about that? Could you give me an example? What is significant about that? And active listening to draw the person out and check for understanding: So, what you’re saying is…, Let me see if I have this right… I stick with asking questions and listening until I can summarize what we call “the third story.” The third story represents all of what is true for me and what is true for Leo. It’s like I have a bucket, and I keep adding things into the bucket. I don’t take anything out and try to solve it yet. I just add things until we’ve collected all of what is true for both of us. “So, to summarize, I need you to listen to the concerns and questions of your teammates and address them. It’s frustrating for you to have to consider other people’s concerns as you’ve already thought it all through. Further discussion is unnecessary, slows you down, and may interfere with you hitting your numbers. Do I have that right?”

I don’t necessarily have to agree with Leo’s perspective, but I need to get to a place where I understand him, where I can summarize his point of view in a way that he says, “yes, that’s it.” And if that’s not it, then I keep asking questions until we get to the core of the issue. It’s not until we reach that point that we can start problem solving.

It’s this final stage of the conversation that is often more comfortable and familiar – generating options and agreeing on a path forward. It’s best if most of the options come from Leo so that he owns how he wants to move forward but I can offer ideas as well. Together we can agree on a plan and next steps. Be sure to build in support and accountability. “What do you need from me to put this plan into action?” “Let’s schedule time to check-in and see how it’s going.”

“So, to summarize, I need you to listen to the concerns and questions of your teammates and address them. It’s frustrating for you to have to consider other people’s concerns as you’ve already thought it all through. Further discussion is unnecessary, slows you down, and may interfere with you hitting your numbers. Do I have that right?”

I don’t necessarily have to agree with Leo’s perspective, but I need to get to a place where I understand him, where I can summarize his point of view in a way that he says, “yes, that’s it.” And if that’s not it, then I keep asking questions until we get to the core of the issue. It’s not until we reach that point that we can start problem solving.

It’s this final stage of the conversation that is often more comfortable and familiar – generating options and agreeing on a path forward. It’s best if most of the options come from Leo so that he owns how he wants to move forward but I can offer ideas as well. Together we can agree on a plan and next steps. Be sure to build in support and accountability. “What do you need from me to put this plan into action?” “Let’s schedule time to check-in and see how it’s going.”

Manage Yourself

Now, is it ever that easy? Of course not. While it’s helpful to have a map for these conversations, no matter how prepared we are, it never goes exactly how we expect. People are complicated and will almost always throw a wrench into the conversation that we never saw coming. Or they’ll do something that seems perfectly designed to get under our skin – raise their voice, roll their eyes, or say that one thing that touches our most sensitive nerve And so, a big part of the discipline of these conversations is having a plan for how we will manage ourselves in the face of the triggers that could knock us off our game. First, we need to be aware that we’re triggered in the first place. Often, we become our irritation, or our anger. Instead, we need to notice it by tuning into our internal signals – I might notice myself thinking “here we go again with the excuses,” or that my breathing has accelerated, or that I’m starting to feel impatient. These signals are like lights on your car’s dashboard. When the “check engine” light comes on, you don’t smash the dashboard – you check under the hood. The same goes for triggers in tough conversations. Get curious about what the signal is telling you and take corrective action to get yourself back on track before you respond. If we don’t notice and manage our triggers, all sorts of unintended behaviours appear, and we can become the worst version of ourselves. Things start to escalate, or the other person withdraws, and we get further and further from a resolution.The Courage to Coach When it Matters Most

Being effective in these conversations requires the very best of us. It takes self-awareness and being a big person. But the 3×4 Coaching model provides everything we need to succeed. We need to enter the conversation with a generous mindset and clarity on our objective. We deliver a clear opening statement to get the conversation off on the right foot and then drop our agenda to explore the other person’s perspective before we jump into problem solving. It isn’t always comfortable, but the goal of coaching isn’t comfort. It’s about challenging someone to reach their highest potential. It requires the courage to speak up, the patience to wade through the discomfort, and the belief that the people you’re coaching are capable of more. Imagination, belief and energy are precious resources that need to be carefully nurtured when high performance is the goal. At the same time, saddling someone with an unattainable target because you don’t want to dampen their enthusiasm risks a catastrophic failure that can destroy self-confidence and trust in the coach. An ambitious but naïve performer setting an unrealistic goal for themselves is commonplace: a direct report applies for a role where they are unlikely to be the successful candidate; an individual you coach sets a performance target for themselves based on their best year ever when headwinds are coming on strong; or your team is running a pilot project that’s very unlikely to get the green light to proceed. How can you communicate belief in the performer, while at the same time protecting them from experiencing what could be a devastating setback?A moment of insight

One such moment for me happened over 20 years ago when I was working as a swimming coach in Thousand Oaks, California. I was coaching an adult swimming group – or as we called them, “Masters Swimmers” – to prepare them for the first competition of the summer. Masters swimming competitions are interesting events: the beer tent opening is as big a deal as the performances in the pool. But, make no mistake, the performances matter to the athletes.“I immediately realized I had made a mistake”I was doing some goal-setting work with an athlete who had recently taken up the sport and asked her what she thought would be a good goal time for her 100-meter freestyle. Her answer was completely unrealistic, so I suggested a much more attainable goal. The smile vanished from her face, her shoulders slumped, and I immediately realized I had made a mistake. In my well-intentioned effort to save this performer from disappointment, I had limited what she could imagine for herself, communicated a lack of belief in her capabilities and cut off a key source of energy.

Don’t fear negative emotion

In that moment, my gut reaction was to spare this person from setting herself up for failure. What I’ve learned is exceptional coaches know that negative emotion is an inherent part of the journey of growth and development. Progress isn’t linear. When people are testing their limits and doing things that they’ve never done before they will experience setbacks from time to time. And when those setbacks occur, they will experience negative emotions such as frustration or disappointment. But people can survive frustration and disappointment. On the other hand, if you encourage them to set safe goals that you know they will achieve, you limit the powerful “pull forward” that comes with imagining what might be possible.Frame a range of outcomes

While negative emotion is a powerful tool, the coach still needs to prevent a devastating failure. Where I suggested a new goal in place of the one my swimmer had set, I could have included it in a range of possible outcomes that framed a realistic performance as a level of success. In practice, this looks like a series of goals that includes the most ideal outcome and also a few other outcomes that are more realistic and attainable.- Goal “A” might represent a nearly perfect result where they execute flawlessly and all the breaks fall their way.

- Goal “B” might represent a good result where they execute relatively well, but not perfectly, and 50% of the breaks fall their way.

- And finally, Goal “C” might represent a result they can live with where they make a few execution mistakes and experience some bad luck in the process.

“Perfectionists often evaluate any imperfect performance as failure”Perfectionists often evaluate any imperfect performance as failure. By working with the performer to set a range of target outcomes in advance, the coach is then in a position to help them evaluate their performance against objective criteria. This often results in the perfectionist being forced to admit that their “failure” was in fact a “good performance” or at worst “one they can live with.”

Blend empathy and accountability

If the performer doesn’t achieve their ideal outcome, help them harness the negative emotion and use it to fuel growth rather than rushing in to try to make them feel better. Do this by first allowing them to sit with the emotion of the moment. Be there to help them process the experience by providing a listening ear. And then, when the performer seems ready, ask them for their thoughts on how to move forward. And then work with them to create a plan to increase the likelihood of an improved result next time.Re-writing history

If I could go back in time and revisit that moment on the pool deck when that athlete suggested an unrealistic goal, what would I do? I would have accepted that negative emotion is a natural part of the growth process. And rather than trying to shield them from the possibility of failure, I would have allowed them to dream about what might be possible. I would have helped them set a range of goals. And if they failed to achieve their ideal outcome, I would have helped them process the disappointment and then channel that energy into the process of getting better. Of course it was that moment of less than stellar coaching, and the resulting disappointment I felt with myself, that ultimately helped me find a better way forward. Negative emotion is an incredibly volatile fuel. Our CEO, Dane Jensen, lays out how to harness its energy for building motivation in his latest article for Harvard Business Review titled Turn Your Team’s Frustration into Motivation. In the article, Dane offers three tools for leaders to motivate people facing a setback:🏷 Label the negative emotion and engage. Right or wrong, giving it a name helps uncover important information that can be used for moving forward. 👏 Feed the self-coach, not the self-critic. Encourage them to look for the opportunity in the crisis. 🛴 Channel energy to action. Use the moment to build a vision of a better future and build clarity around what it takes to get there.

Strong leaders don’t shy away from negative emotions. They lean into them and help their people use them to recover and grow. Click here to read the article on hbr.org. In 2002, the Canadian Women’s National Hockey Team entered the Olympic Games in Salt Lake City in an unfamiliar position: as underdogs. They had not hit their stride as a team, their confidence had taken a hit, and emotions were at risk of boiling over. In eight head-to-head games against the Americans leading up to the Olympics, Canada had lost all eight. For many players, it was hard to avoid memories from four years earlier when the team had lost to the Americans in the gold medal game. Jayna Hefford, who was playing in the first Games of her Hall of Fame career, recalls the point when the stress and emotion came to a head: “There was an intense conversation in the dressing room with the team. A lot of people had a lot to say about things we needed to do and how we were going to get better, and we realized that a lot of what was happening was the blame game.”“We realized that a lot of what was happening was the blame game.”Through a frank, players-only discussion the team was able to come together, but the conversation could have gone a number of different ways. It stayed on track because the team was prepared – mentally and emotionally – to have performance conversations under pressure and surface a number of issues the team needed to resolve. And that preparation turned out to be an important stepping stone to winning gold in Salt Lake City.

Training the bomb squad

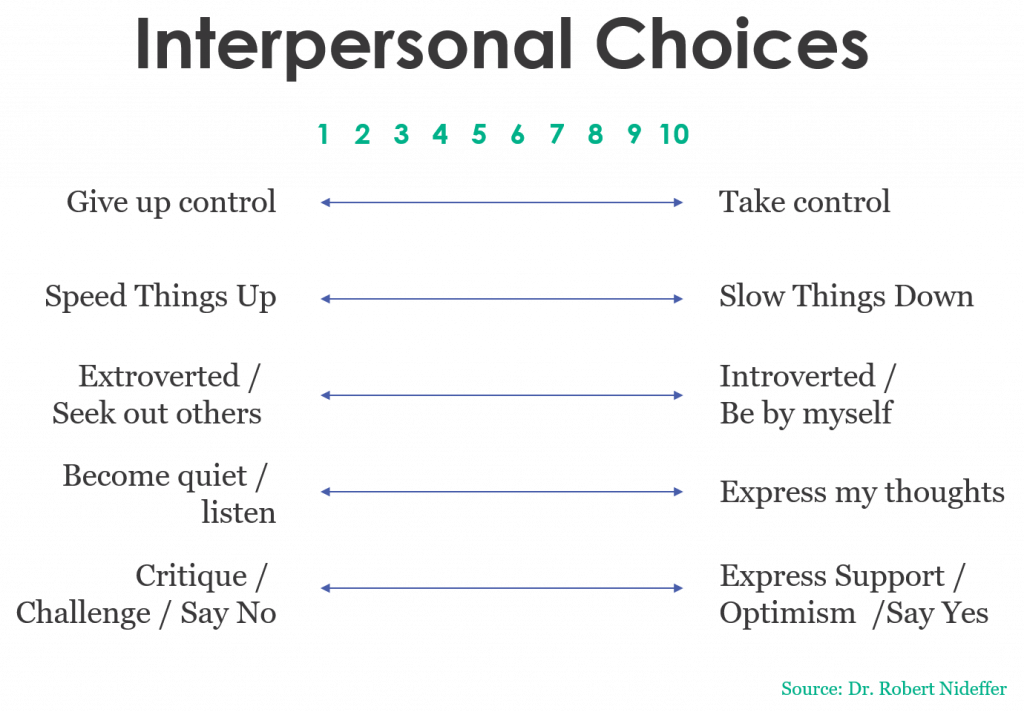

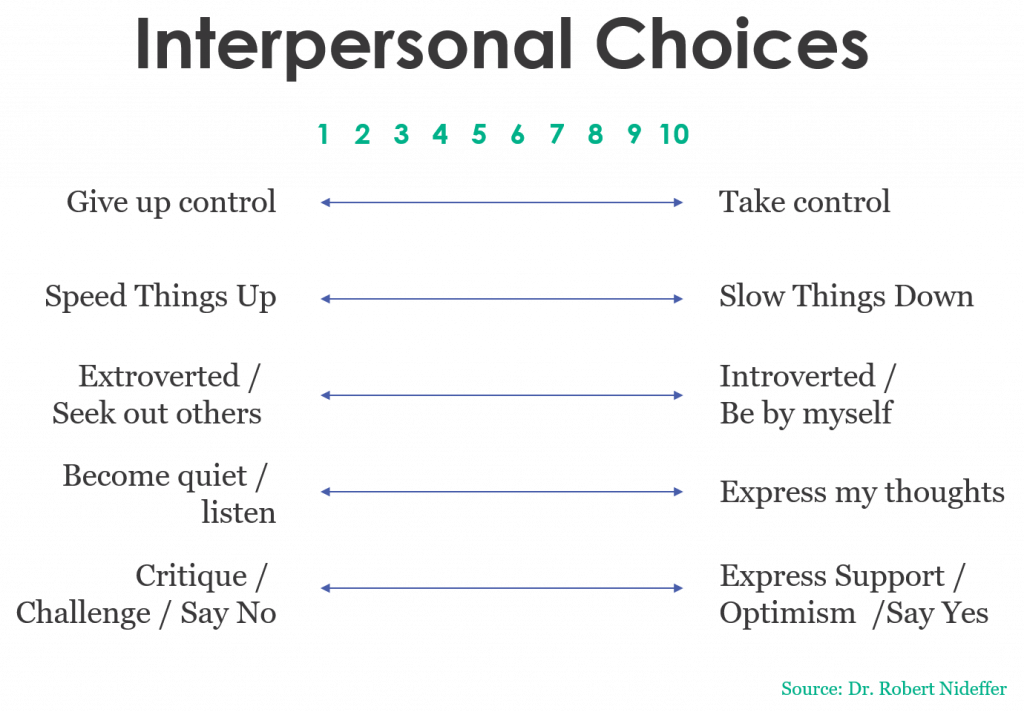

Handled poorly, team communication under pressure can lead to combustion. And just like you wouldn’t get success as a bomb disposal technician going in without their toolkit, you won’t find success in communicating through tense situations if your team isn’t prepared. The advantage the women’s team had that allowed them to emerge from that conversation united was a deep awareness of their communication tendencies and systems to counteract the counterproductive ones. They had laid the foundation for performance conversations in good times so that they could happen and be productive when the difficulty hit. In other words: they had a tool kit and they knew how to use it.“The biggest opportunity for meaningful growth is often to increase self-awareness and strengthen their ability to communicate productively when under pressure.”We’ve worked with hundreds of teams in elite sport and business, including the last four medal-winning Canadian women’s hockey teams. One of the things we’ve learned is that when teams are already operating at a high level, the biggest opportunity for meaningful growth is often to increase their self-awareness and strengthen their ability to communicate productively when under pressure. To support this, we’ve developed a process to help teams become more aware of their tendencies, develop systems and practice performance conversations anytime. At the heart of this process is a tool called the TAIS – The Attentional and Interpersonal Styles inventory. The TAIS was developed for use by Navy SEALs and Olympic athletes, and we’ve found it to be an incredibly valuable tool for diagnosing communication challenges on all kinds of teams. When the pressure is on, when teams are in the midst of setbacks and failure, individuals will fall back on their default communication styles.

Five communication choices

The author of the TAIS, Dr. Robert Nidefer, showed that people make five choices over and over in the course of a conversation. These choices are informed by their tendencies on five dimensions.

Cut the right wire

Every team will have members with different tendencies. Ultimately, it’s not the tendencies that matter; it’s the level of awareness team members have of their tendencies, and the systems they put in place to leverage their strengths and weaknesses in the heat of the moment. The highest performing teams we work with take three critical steps in preparing for productive communication under any circumstances.Acknowledge the “I” in team

Great coaches know that the phrase “there is no I in team” is a myth. Every individual makes their own contribution – and without self-awareness, people can’t adjust. That’s why the first step in your team’s communication action plan is to encourage every individual to build self-awareness across these five choices. By knowing and understanding their default tendencies, team members can begin to recognize their behaviour and course-correct when necessary for the good of the team.Connect to the “we” of the team

It’s advantageous to know your individual tendencies, and the value is multiplied when that information is shared with everyone on the team. When you raise the waterline of team awareness, everyone can work on the same communication system. Team members can see the intent behind the behaviors their teammates exhibit. The process can be incredibly difficult; Team Canada Captain Hayley Wickenheiser called sharing her profile with her team-mates, “the most stressful part of the 4-year [Olympic] quadrennial.”Come together as a team

Armed with knowledge of self and others, teams can come together and translate self-awareness into action. When pressure hits, if everybody on the team has the tendency to get louder, express their thoughts and try to take control of the conversation, the team can make decisions in advance to decide who’s going to take control when issues arise. By having these conversations earlier, teams can build systems to fall back on when the pressure is turned up.Preventing detonation

The next time you’re headed into a potentially high stakes conversations, use the five choices below to carry out a short 3-step preparation exercise:

1. Plot your default tendency on each of the five scales – given your past history, where are you most likely to fall?

2. Where would you ideally like to be as you head into this specific interaction?

3. What are the gaps between your ideal and default style? What actions will you take to ensure you are at your ideal?

Repurpose the fuel for growth

We’ve said before that negative emotion is volatile fuel. Improperly handled, it can lead to combustion. Used properly, it can lead to high performance. Team communication must go beyond just staying cool during difficult times. Teams must use communication to understand and lean in to their negative emotions, uncover what the emotions are telling them, and frame it as an opportunity for growth. This is what happened with the women’s team in 2002. They prepared to have productive communication at all times, and used the tools they learned to find the opportunity for growth at a moment when it could have blown up. Jayna Hefford explains: By understanding your individual communication style, sharing your tendencies with the team and proactively planning to address potential faults, your team can find its way through difficult times and not just safely diffuse difficult situations but find new strength and opportunity for higher performance in the process.By Dane Jensen / CEO, Third Factor

All teams suffer setbacks. What separates resilient teams from the rest is how they respond. Resilient teams come back stronger after failure because leaders and team members lean into the negative emotions that inevitably accompany setbacks and use the energy under those emotions to fuel recovery.Negative emotion is volatile fuel

Heading into the women’s World Cup in 2011, Canada’s national soccer team was one of the favourites. Two weeks later, they were knocked out of the round robin in a 4-0 defeat to France and headed home without winning a game – finishing dead last.“It wasn’t going to define us”Team Captain Christine Sinclair talked about feeling “humiliated” – like they had let down the country. And yet just one year later, the same team outperformed at the London Olympics to win Canada’s first ever medal in soccer. “We knew what we were capable of and just because we had one bad tournament it wasn’t going to define us,” said Sinclair. The head coach of the Women’s National Team, John Herdman, spoke about how the team was “an easy group to motivate” because they had just suffered such a crushing defeat. Negative emotion can be powerful fuel for positive response. It can provide ‘bulletin board material’ that leads to determination, and ultimately harder work and higher standards. But negative emotion is highly volatile fuel. If not handled correctly, it can trigger a negative feedback loop that leads to the blame game and teams that end up either combusting or just detaching.

Three Jobs for Leaders of Resilient Teams

We’ve observed that leaders of resilient teams are able to trigger the positive feedback loop from negative feedback by doing three things differently than leaders of less resilient teams: 1. Lean into negative emotion Leaders of resilient teams don’t retreat from negative emotion. They don’t try to rescue people from it and make them feel good. Rather, they use it for its developmental potential. The psychologist Roberto Assagioli has said, “a psychological truth is that trying to eliminate pain merely strengthens its hold. It is better to uncover its meaning, include it as an essential part of our purpose and embrace its potential to serve us.” When leaders try to reassure people or make the pain go away, they rob it of its power. It is better to acknowledge the pain and embrace it so that it can be used to fuel growth.“As painful as it feels now, it will help him.”So, what does ‘leaning in’ look like? Consider “the shot.” Kawhi Leonard’s quadruple bouncing Game 7 buzzer beater was a moment of euphoria for Toronto. On the other side, however, it was a devastating moment for a young Philadelphia 76ers team featuring 25-year-old star Joel Embiid, who left the court in tears. When asked about the emotional response of Embiid in the post-game press conference, Philadelphia head coach Brett Brown said, “As painful as it feels now, it will help him. It will help shape his career.” Rather than shying away from the pain, comforting Embiid and trying to lessen the sting, Brown leaned into it and helped his young player see it as a growth opportunity – a sign that he needed to work harder. 2. Frame negative emotion differently Leaders of resilient teams have a different answer to the question “what is this pain telling us?” than leaders of less resilient teams. They frame pain as a signal that they aren’t there yet – rather than a sign that they aren’t good enough. As a result of this framing, resilient teams respond to negative emotion with determination. They get committed to the challenges they face by exerting control where it matters: their own effort. After a lacklustre season heading into Salt Lake City in 2002, the Canadian women’s hockey team held a player’s only meeting where they came up with the acronym WAR, for ‘We Are Responsible.’ As 4-time gold medalist Janya Hefford reports, “there was a lot of the blame game going on”– and the WAR framing helped them redirect attention away from the officiating, their opponents, etc. and towards what they were responsible for. Ultimately, this perspective proved vital in overcoming 8 straight penalties in the Gold-Medal game to triumph. 3. Channel negative emotion After embracing negative emotion and finding its meaning, teams and their leaders must still channel the emotion into positive outcomes. Our founder, Peter Jensen, will often ask teams who have suffered failure one powerful question: “What are we going to do with the energy under this emotion?” it’s easy to channel emotion into what Ben Zander has called “the conversation of no possibilities” and allow the dangerous side of negative emotion affect to take over. Channeling negative emotion productively requires individuals on teams to take responsibility for redirecting energy towards growth and hard work.