Kindness Is the Mechanism That Lets Standards Hold

When choosing who to work with, one thing mattered most to the brothers. “Skills can be learned,” Brian says, “but the right compatibility is [most] important.” For Brian and Robin, compatibility meant being able to handle feedback without eroding trust. It wasn’t about being agreeable, it was about keeping standards high while delivering feedback with kindness. “There could be criticisms, there can be hard conversations,” Brian explains. But when feedback came with “kindness in their hearts and how it’s being presented,” it became “much easier to listen to it and to debrief, and figure out a better way forward.” That difference mattered for learning. With trust in place, someone could say, “Hey, I think if you do something this way, you’ll be faster,” and it would be heard as help. As Brian says, “we all get better together.” Robin noticed the same effect. Strong trust meant “less micromanaging.” Standards didn’t drop; roles were clear, intentions were trusted, and learning could continue under pressure. Here’s Brian sharing about the importance of kindness to their culture:Kindness Can Raise the Bar

One of the most important moments in Brian’s Paralympic career happened because a competitor took the time to help him. Early in his Para Nordic career, Brian sometimes raced without a guide. In one event, he finished just “30 seconds behind the top guy in the world.” Afterward, the German athlete and his guide told him, “You need to have a guide, because today with a guide, you might have won.” Brian remembers thinking, “Why would another nation be helping me out on this?” The answer was simple: they were “just excited to have competition.” That advice changed Brian’s path. Because of that conversation, he asked Robin to guide him, beginning “10 years of pretty fun work racing together.” Sometimes kindness doesn’t make sport easier. It makes it better. On why others helped them out to raise the bar:Trust Is Built in the First Failure, Not the First Success

Their first World Cup together took place at the Salt Lake City Olympic course in March 2001. It was unusually warm – about 15 Celsius, Robin recalls – and the snow was wet and unpredictable. On a fast downhill, something went wrong. Robin reached the bottom and realized, “Brian’s not there.” He waited, then started hiking back up the course. He heard Brian yelling. What he saw first wasn’t Brian, but “a ski sitting off the edge of the trail.” Brian had caught an edge in the “sloppy snow,” gone off course, and ended up “hanging off of a tree upside down.” Robin climbed down, removed the skis, and pulled him back up. From Brian’s side, he stepped outside the track to get a push and hit the “mashed potatoes” snow: “My ski stopped and I kept going.” The tree became “the only thing stopping me from sliding headfirst down a steep mud slope.” He held on and waited for Robin. “I figured he’d eventually figure out I wasn’t there,” Brian says. Robin later called it “a very big failure on day one.” What mattered was what followed. “We laughed about it.” No blame. No anger. That moment set the tone. Trust wasn’t automatic – even between brothers. It was built through shared experience and protected by how mistakes were handled. Kindness showed up early, not as softness, but as steadiness. Here’s Robin sharing their early guiding failures:Autonomy in Preparation. Alignment in Execution.

The McKeevers succeeded because they didn’t pretend they were the same athlete. As Robin explains, “We have overlapping roles that work together … we have the same end goal, but we still need to arrive there in slightly different ways.” That showed up in training. “We have our own training programs,” he says. “It’s not exactly the same, but we still need to arrive at the same point where we can ski together, race together, and communicate in order to achieve a team victory.” Brian puts it plainly: “I can ski by myself. Robin can ski by himself, but he’s there to help me. And we are winning this together. We’re not doing this individually.” Giving each other space reduced friction. Coming together at the right moments kept them aligned. Trust and looking out for each other were the glue that made both possible.What Leading With Kindness Looks Like in Practice

The McKeevers’ story reveals three practical behaviours that translate directly to leadership and teams:01.

Reset without blame when something goes wrong.

02.

Deliver feedback as performance support, not personal judgment.

03.

Clarify ownership to reduce micromanagement and create alignment.

01. Reset without blame when something goes wrong

When Brian crashed off the course in Salt Lake City, the response wasn’t panic or finger-pointing. Robin described the day as a failure, but one they laughed about and moved on from. That response preserved trust in a moment where it could have fractured.02. Deliver feedback as performance support, not personal judgment

Hard conversations were unavoidable, but when framed with respect, people stayed receptive. The feedback that mattered most was specific and performance-focused: if you do this differently, you’ll be faster.03. Reduce micromanagement by clarifying ownership and alignment

Trust allowed Brian and Robin to prepare in their own way while still arriving at the same execution point. Different paths. Same outcome. This is kindness without lowering the bar: respect that keeps people engaged, paired with precision that drives improvement. In the McKeevers’ case, kindness turned trust into medals, and a partnership into a lasting competitive advantage. —- Brian will be coaching the Canadian para-Nordic team as they go for gold in Milan-Cortina starting on March 10 (see the team schedule here), while Robin will be supporting the Canadian Nordic team as a member of the coaching staff.Build Resilience In Your Organization

Bring the skills that elite athletes use to build resilience and perform under pressure to your organization. Contact us to learn more about our resilience programs.

That preparation mattered in Sochi. When pressure mounted, the team didn’t fracture emotionally. They had already agreed on how they would behave.

You Perform How You Prepare

A persistent myth about high performance – whether in athletes or business leaders – is that resilience appears when it’s needed most. The reality is simpler: it shows up only to the extent that it has been rehearsed. Months before the Olympics, Jensen met with the team before a game against a strong AAA boys’ team from Brandon, Manitoba. The discussion wasn’t about winning that night. Instead, it focused on a specific scenario they could face: being down 2-0 in the third period. The players began by talking through how they would manage the clock. “You think about it in 10-minute segments,” Jensen explains. “You break it in half … and break it down into achievable things.” He then narrowed the window. What if there were only five minutes left? Now it became two-and-a-half-minute sequences. Smaller problems. Clearer focus. The emphasis was not on emotion or outcome, but on behaviours the team could control under pressure. So when Team Canada found itself down two goals with around seven minutes left in the Sochi gold medal game, the players weren’t overwhelmed. The situation felt familiar. They had been there before and knew how to respond.

“Stay Positive” Is Not a Strategy

Another subtle but critical shift was Jensen’s refusal to let the team sidestep uncomfortable realities. When asked how they would respond individually late in a close game, players emphasized the importance of staying positive and supporting their teammates. Jensen pushed back. “The coach shortens the bench. And so you’re irritated,” he told them, adding players who weren’t getting ice time would feel frustrated and lose focus. Pretending otherwise wouldn’t make that problem go away. So the team discussed what that “irritation” might feel like and how players could still support their teammates on the ice. By talking about those moments in advance, they normalized them. Falling behind stopped being a psychological threat and became a known condition with a known response. That preparation mattered in Sochi. When pressure mounted, the team didn’t fracture emotionally. They had already agreed on how they would behave.Normalize Adversity Instead of Hoping It Won’t Appear

After the gold medal game, head coach Kevin Dineen summed up his team in a few words: They never gave up. From Jensen’s perspective, there was more to that explanation. “They didn’t give up because that’s who they were,” he says. “We’d done a lot of work on team vision and culture. But we’d also simulated what they would need to do.” The team didn’t treat adversity as an anomaly. They treated it as an inevitability. By rehearsing the moments most likely to derail them – shortened benches, frustration, time pressure – they removed surprise from the equation. And when surprise disappears, performance improves. The Sochi gold medal didn’t come from belief summoned in the moment. It came from preparation that made the moment feel familiar.Pre-Plan for Adversity

You don’t need an Olympic stage to apply these lessons. The same approach Team Canada used to win gold works in business, leadership and life. Here’s how to get started:- Identify two to three scenarios that are most likely to derail your team.

- Break each scenario into smaller, controllable steps to solve, rather than treating it as one overwhelming problem.

- Decide in advance what you will think, say, and do when those moments show up.

- Choose simple imagery or verbal cues that help ground focus and regulate emotion under pressure.

Key Insights:

-

Resilience is not a personality trait; it is a trained response to pressure.

-

Breaking high-stakes situations into smaller, controllable segments reduces cognitive overload and sharpens execution.

-

Avoiding negative scenarios creates fragility; rehearsing them creates confidence.

-

Teams perform better under pressure when they normalize adversity instead of treating it as failure.

-

Preparation replaces hope with clarity.

Build Resilience In Your Organization

Bring the skills that elite athletes use to build resilience and perform under pressure to your organization. Contact us to learn more about our resilience programs.

Mel Davidson

Debbie Low

Jesse Lumsden

Tracy Wilson

A team’s energy comes from within

A while back I was leading a Self-Aware Team program for the coaches and support staff of a team that was preparing to represent Canada at the Winter Games in Beijing. An important part the program is an exercise in which team members create “player cards” containing key insights they’ve learned about themselves through the program. The group then comes together in a Zoom call to share those insights and give and get feedback. Like so many others, this group had been through an incredibly taxing year. Because of the pandemic, the team had to expend significantly more energy than it ordinarily would to create effective training opportunities for the athletes. Quarantines and “bubbling” rules had forced individuals to spend months at a time on the road, adapting to new routines and away from their families. And uncertainty over everything from health and testing to the potential fate of the games loomed over it all.“The ways they brought energy were as diverse as the people themselves.”As the group shared their player cards, it quickly came to light that a number of different members of this team had been significant “energy givers” through this difficult time. And the ways they brought energy were as diverse as the people themselves.

- One senior leader on the team created energy in the more traditional way that many leaders do: by envisioning a compelling opportunity, mapping out a plan to get there and leading the charge towards it.

- Another team member helped bring lightness to the daily grind by noticing and pointing out funny moments, breathtaking views, or interesting aspects of their surroundings. These moments created mini-breaks that relieved tension and reminded the team of the unique and special journey they were on together.

- Another contributor was celebrated for their “can-do attitude.” This individual had a “big personality” with a healthy dose of confidence who led by example and encouragement. Their jokes, positive energy and infectious smile helped the team forge ahead with a belief that they could prevail when they were hit with a setback or success seemed a long way off.

- Yet another had taken on the role of a confidante and created a safe, non-judgmental space for people to bounce ideas, vent frustrations and seek advice when they needed to gain perspective on a situation (or person) that was creating challenges.

Three energizing principles

In listening to the group share their feedback, I was struck by three things: Energy is found in diversity. During the discussion I heard multiple different ways that multiple different people infused the group with energy. Some provided big boosts, other provided steady nudges. Some energized all team members. Others were more critical in sustaining a handful of specific individuals. Some were helpful at the start to get the flywheel moving forward. Others stepped in during negative moments to break tension and redirect focus when forward movement was stalled. Each team member’s contribution could stand on its own, but put together they added up to more than the sum of their parts. Energizing the team is everyone’s responsibility. No single contributor can create enough energy on their own to sustain a team; the demands are simply too vast. Everyone on the team shares some responsibility for energizing their teammates. The team leader’s job is to create the conditions that allow it to happen. Feedback is of key importance. In many cases, the “energy givers” were surprised to learn the value of what they provided. In fact, some had mistakenly believed that the very behaviors that others found energizing were irrelevant or a distraction. If not for the reinforcement they received during the session, many had been planning to curtail some of those behaviors moving forward. And, if that had taken place, then valuable sources of positive energy would have simply faded away because people were unaware.Energize your team

Every leader needs to create an environment that enables their people to perform. And energy is a critical part of that environment. But it’s not the leader’s role to provide that energy all on their own. Instead, the best leaders create the conditions for “energy givers” to thrive.“Create a clear image of what it looks like to be an energy giver.”Start by setting the expectation that energy is a team responsibility. Work with your people to create a clear image of what it looks like to be an “energy giver” and what behaviors will move the team’s energy level in a positive direction. Help your team surface the different ways “energy givers” sustain the team in tough moments. Make it a part of your regular check-ins to ask people what’s contributed to their energy over the past week and encourage open discussion when appropriate. Finally, provide opportunities for regular feedback and recognition so that each “energy giver” knows what to keep doing. This feedback can come from you as a leader, but people should also hear from their peers. Effective feedback recognizes the behavior, communicates its impact, and encourages the person to continue. With this approach, a leader can create more energy on their team than they could ever hope to do alone, while at the same time helping their people to stay engaged and motivated through whatever may come. Editor’s note: This article was first published on April 14th, 2020, just a few weeks into the COVID-19 pandemic. While the context may have changed, your plays as a leader are still the same.

In this article:

Four imperatives for leaders in times of uncertainty

- Invest in relationships. Try to find “30 seconds for every player, every day.”

- Think small. Annual plans are out – ensure your people are clear on what the work expectations are for today.

- Make a habit of catching people doing something right. Reinforcing feedback is vital to fostering engagement.

- Coach the whole person. With personal life and work life collapsing, now is the time to demonstrate empathy.

It’s all about the relationship

When people go through difficult times together, they can emerge more connected – but only if they’re conscious about it. Difficult times can also lead to fracture. As a leader, it’s your job to step back and really think about how you are building and deepening relationships with your people in this new environment. Take the time to check in with your people and listen to them. Take some time to step back and see what you’re going through as impartial observers and acknowledge that it’s hard. These are unprecedented times and the effort you make to stay connected with your people can make a huge difference. Coach Roy Rana of the Sacramento Kings spoke with us about how building relationships is intentional. There is an intention to communicate, to make the person feel connected, to ensure they know they have your attention. He talks about the little things that he does to accomplish this. In the video below, he lays out the wonderful challenge he sets for himself of “30 seconds every day for every player”: Rana’s Strategies are for basketball – not your environment. So what would work for you? What are the little ways you can connect with your people to communicate that you are thinking of them and you care?The game has changed

By now, every workplace has been impacted by COVID-19. The game has changed, and clarity needs to be re-established. Your team needs new skills and mindsets so that you can get through this together.“We can’t go back, only forward.”Ask yourself what your team needs for their new playbook. Do your people know what the work expectations are today? Timelines are different. Things change quickly so clarity is always evolving. Think short term and help them find focus. Do they know what other people need from them? Are they aware of how your goals have shifted? Especially if your team is working differently than they’re used to, over-communication is impossible when it comes to these things. Your team also needs clarity on what your organization’s values look like in this reality. Not just the vague, nice-sounding words – what they actually look like. If you value safety, how are you acting on that value? If you value team, how are you making sure that no one’s feeling isolated? Get together as a team to discuss your values and think through how you’re living up to them at this time. Through all of this, recognize that as a coach you need to meet your people where they’re at. Some team members might be juggling kids and other family constraints. They may even be caring for someone who is sick. Give them real clarity on how your team can work well together in a way that’s not going to make anyone feel criticized, judged or guilty. Have empathy for what they’re going through and use humour to help people feel at ease. Some team members (and perhaps even you) may be thinking they just need to hold on for a little bit longer until things get back to normal. That thinking will not serve them or the organization well. When companies face disruption, the ones who try to ignore it or find a way to hang on to their old ways of doing things don’t fare well – think Blockbuster. We can’t go back, only forward.

New plays for a new game

When the game changes, you can’t expect to get the same results from the same behaviours. As a coach, your goal is to help your people succeed in their new reality – and this means helping them get up to speed on the skills that will support the new expectations as well as discouraging the old behaviours that are no longer productive. This is all about consistent feedback and communication, and feedback is a challenge when you can’t see what people are doing. For the coachee, the lack of visibility can lead to frustration and unnecessary roadblocks that can harm engagement. Make a habit of checking in frequently with each team member to support their development. This isn’t about micromanaging or checking up on them; it’s about making sure they’re not sitting alone frustrated because something’s blocking their progress. If that sounds like a big job, that’s because it is. Coach Rana told us about how making time for each and every team member is a challenge even as a professional coach. And he offered this advice for keeping the connection alive even when it feels like you’re too busy.Out of sight, not out of mind

If what I’m doing can’t be seen, how do I know if it’s valued or appreciated? This is one of the challenges your people are facing as they transition to a new reality. People need to know that what they do has value, so giving appropriate recognition is more important now than ever. This doesn’t mean handing out awards and prizes. It’s about looking for the bright spots – things that are going well, little wins, positive behaviours – and acknowledging them. You might recognize a team member who creates a shared space for everyone to connect, or someone who volunteers to take on a task for another team member they see struggling. It’s also vital to recognize that people need to feel connected and not isolated. Make every conversation a coaching one. Even simple questions like “how are things going today” have value for a coach. As you explore the answer, you can uncover the information you need to find possibilities and build commitment to a solution. When people are worried, anxious or afraid they’re harder on themselves than ever. Having the coach remind them of who they are at their best brings tremendous energy.Be ready for the human element

Behind all this is a real humanitarian challenge. As time goes on, the people on your team may become sick, need time off to care for loved ones, or worse. Loss is going to look very different for different people – it can be loss of a loved one, income, or something else. As a coach you have a role to play in supporting your team members as they recover from whatever their loss may be. The temptation is to think that when someone is in pain over their loss that bringing it up will cause undue pain by reminding them of it. Just keep to your work and ignore it. And that’s like the monster under the bed for a little kid. As long as the kid believes there’s a monster under the bed it gets bigger and bigger. The longer it goes, the bigger it gets.“When loss isn’t acknowledged, it feels like it’s been dismissed.”This is true on both sides of the relationship. In Sheryl Sandberg’s book, Option B: Facing Adversity, Building Resilience, and Finding Joy, she talks about how the hardest part of going back to work after losing her husband was the silence. When loss isn’t acknowledged, it feels like it’s been dismissed. And a significant loss being dismissed feels really bad. You don’t need to be a counsellor or have all the answers, and there’s no secret formula for how to deal with these times. Your job as a coach is to bring things to the surface and give people permission to talk about it if and when they want.

Help people get better at whatever it is they do

We often define a coach’s core job as this: help people get better at whatever it is they do. We call this developmental bias, the idea that a coach is always biased toward developing their people no matter what the circumstance. As the “whatever it is they do” continues to change and evolve over the coming months, and probably years, you have an opportunity to help your people stay engaged and rise to the occasion. By maintaining and building relationships, building clarity around what’s expected, building competence in new ways of working, and recognizing the all of what is happening, you can show your people that you’re on their side and help your entire team emerge stronger for it. In 2002, the Canadian Women’s National Hockey Team entered the Olympic Games in Salt Lake City in an unfamiliar position: as underdogs. They had not hit their stride as a team, their confidence had taken a hit, and emotions were at risk of boiling over. In eight head-to-head games against the Americans leading up to the Olympics, Canada had lost all eight. For many players, it was hard to avoid memories from four years earlier when the team had lost to the Americans in the gold medal game. Jayna Hefford, who was playing in the first Games of her Hall of Fame career, recalls the point when the stress and emotion came to a head: “There was an intense conversation in the dressing room with the team. A lot of people had a lot to say about things we needed to do and how we were going to get better, and we realized that a lot of what was happening was the blame game.”“We realized that a lot of what was happening was the blame game.”Through a frank, players-only discussion the team was able to come together, but the conversation could have gone a number of different ways. It stayed on track because the team was prepared – mentally and emotionally – to have performance conversations under pressure and surface a number of issues the team needed to resolve. And that preparation turned out to be an important stepping stone to winning gold in Salt Lake City.

Training the bomb squad

Handled poorly, team communication under pressure can lead to combustion. And just like you wouldn’t get success as a bomb disposal technician going in without their toolkit, you won’t find success in communicating through tense situations if your team isn’t prepared. The advantage the women’s team had that allowed them to emerge from that conversation united was a deep awareness of their communication tendencies and systems to counteract the counterproductive ones. They had laid the foundation for performance conversations in good times so that they could happen and be productive when the difficulty hit. In other words: they had a tool kit and they knew how to use it.“The biggest opportunity for meaningful growth is often to increase self-awareness and strengthen their ability to communicate productively when under pressure.”We’ve worked with hundreds of teams in elite sport and business, including the last four medal-winning Canadian women’s hockey teams. One of the things we’ve learned is that when teams are already operating at a high level, the biggest opportunity for meaningful growth is often to increase their self-awareness and strengthen their ability to communicate productively when under pressure. To support this, we’ve developed a process to help teams become more aware of their tendencies, develop systems and practice performance conversations anytime. At the heart of this process is a tool called the TAIS – The Attentional and Interpersonal Styles inventory. The TAIS was developed for use by Navy SEALs and Olympic athletes, and we’ve found it to be an incredibly valuable tool for diagnosing communication challenges on all kinds of teams. When the pressure is on, when teams are in the midst of setbacks and failure, individuals will fall back on their default communication styles.

Five communication choices

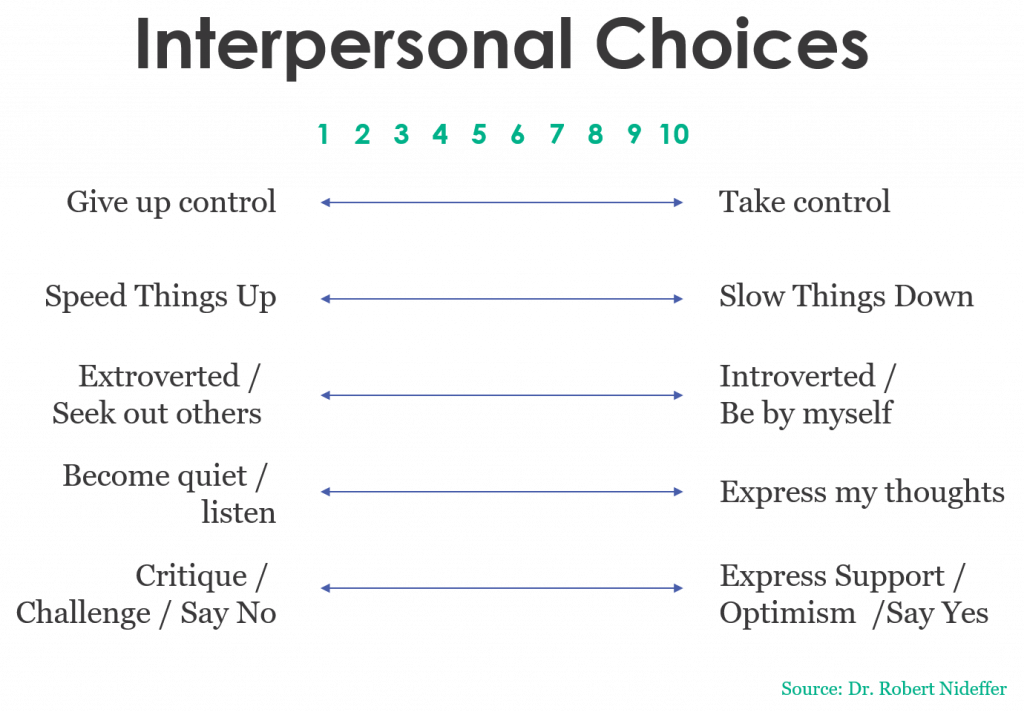

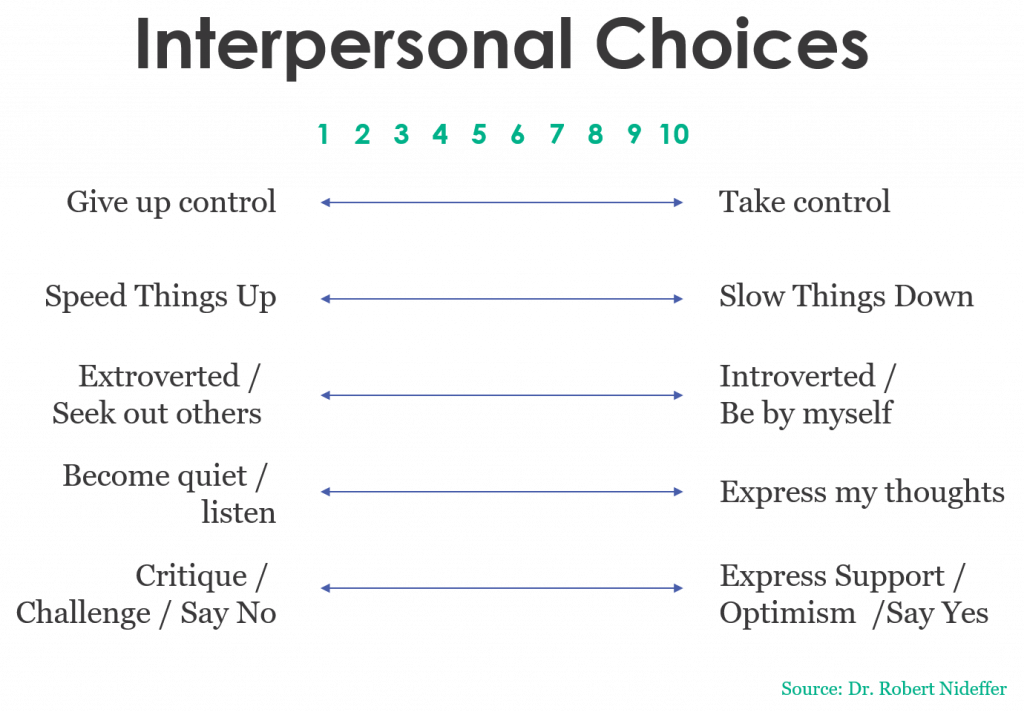

The author of the TAIS, Dr. Robert Nidefer, showed that people make five choices over and over in the course of a conversation. These choices are informed by their tendencies on five dimensions.

Cut the right wire

Every team will have members with different tendencies. Ultimately, it’s not the tendencies that matter; it’s the level of awareness team members have of their tendencies, and the systems they put in place to leverage their strengths and weaknesses in the heat of the moment. The highest performing teams we work with take three critical steps in preparing for productive communication under any circumstances.Acknowledge the “I” in team

Great coaches know that the phrase “there is no I in team” is a myth. Every individual makes their own contribution – and without self-awareness, people can’t adjust. That’s why the first step in your team’s communication action plan is to encourage every individual to build self-awareness across these five choices. By knowing and understanding their default tendencies, team members can begin to recognize their behaviour and course-correct when necessary for the good of the team.Connect to the “we” of the team

It’s advantageous to know your individual tendencies, and the value is multiplied when that information is shared with everyone on the team. When you raise the waterline of team awareness, everyone can work on the same communication system. Team members can see the intent behind the behaviors their teammates exhibit. The process can be incredibly difficult; Team Canada Captain Hayley Wickenheiser called sharing her profile with her team-mates, “the most stressful part of the 4-year [Olympic] quadrennial.”Come together as a team

Armed with knowledge of self and others, teams can come together and translate self-awareness into action. When pressure hits, if everybody on the team has the tendency to get louder, express their thoughts and try to take control of the conversation, the team can make decisions in advance to decide who’s going to take control when issues arise. By having these conversations earlier, teams can build systems to fall back on when the pressure is turned up.Preventing detonation

The next time you’re headed into a potentially high stakes conversations, use the five choices below to carry out a short 3-step preparation exercise:

1. Plot your default tendency on each of the five scales – given your past history, where are you most likely to fall?

2. Where would you ideally like to be as you head into this specific interaction?

3. What are the gaps between your ideal and default style? What actions will you take to ensure you are at your ideal?

Repurpose the fuel for growth

We’ve said before that negative emotion is volatile fuel. Improperly handled, it can lead to combustion. Used properly, it can lead to high performance. Team communication must go beyond just staying cool during difficult times. Teams must use communication to understand and lean in to their negative emotions, uncover what the emotions are telling them, and frame it as an opportunity for growth. This is what happened with the women’s team in 2002. They prepared to have productive communication at all times, and used the tools they learned to find the opportunity for growth at a moment when it could have blown up. Jayna Hefford explains: By understanding your individual communication style, sharing your tendencies with the team and proactively planning to address potential faults, your team can find its way through difficult times and not just safely diffuse difficult situations but find new strength and opportunity for higher performance in the process. When the trajectory of your life hangs in the balance of one critical moment – when your heart is racing, your palms are sweaty, and your breathing is ragged – how do you nail it? Few people are better qualified to answer this question than Olympic skating legends Brian Orser and Tracy Wilson. As athletes, they carried the weight of a nation at the 1988 Olympic Games in Calgary – entering as a reigning world champion and 7-time Canadian champion, respectively. Competing in front of a home crowd with incredibly high expectations, Brian and Tracy won 2 of Canada’s 5 medals in Calgary. Today, Brian and Tracy are coaches to a new generation of elite skaters from around the world at the Toronto Cricket Club. They’ve produced gold medalists for the last 3 Olympic games and currently coach the reigning Olympic men’s champion, Yuzuru Hanyu of Japan, and the reigning Olympic women’s silver medalist, Evgenia Medvedeva of Russia. As athletes and coaches, Brian and Tracy have delivered exceptional performances in moments of intense pressure. In this video series, they shine some light on their experience performing under pressure and coaching athletes to perform under pressure, and reveal simple strategies you can use to be at your best in your own most critical moments.Brian Orser describes the media frenzy and inescapable layers of pressure he felt leading up to the ‘Battle of the Brians’ on home ice at the 1988 Calgary Olympics.“There was a media frenzy”

Tracy Wilson shares how she practiced the emotional moments in advance of competition at the 1988 Olympic Games in Calgary.“What got me so excited was representing Canada”

Brian Orser talks about how he established and practiced routines for any situation, whether he had to skate first or wait around to skate 6th.“We were prepared for any scenario”

Tracy Wilson explains how leaning into emotions can help performers diffuse tension and how coaches can use communication to help their team members perform at critical moments.“I hate this part”

By Dane Jensen / CEO, Third Factor

All teams suffer setbacks. What separates resilient teams from the rest is how they respond. Resilient teams come back stronger after failure because leaders and team members lean into the negative emotions that inevitably accompany setbacks and use the energy under those emotions to fuel recovery.Negative emotion is volatile fuel

Heading into the women’s World Cup in 2011, Canada’s national soccer team was one of the favourites. Two weeks later, they were knocked out of the round robin in a 4-0 defeat to France and headed home without winning a game – finishing dead last.“It wasn’t going to define us”Team Captain Christine Sinclair talked about feeling “humiliated” – like they had let down the country. And yet just one year later, the same team outperformed at the London Olympics to win Canada’s first ever medal in soccer. “We knew what we were capable of and just because we had one bad tournament it wasn’t going to define us,” said Sinclair. The head coach of the Women’s National Team, John Herdman, spoke about how the team was “an easy group to motivate” because they had just suffered such a crushing defeat. Negative emotion can be powerful fuel for positive response. It can provide ‘bulletin board material’ that leads to determination, and ultimately harder work and higher standards. But negative emotion is highly volatile fuel. If not handled correctly, it can trigger a negative feedback loop that leads to the blame game and teams that end up either combusting or just detaching.

Three Jobs for Leaders of Resilient Teams

We’ve observed that leaders of resilient teams are able to trigger the positive feedback loop from negative feedback by doing three things differently than leaders of less resilient teams: 1. Lean into negative emotion Leaders of resilient teams don’t retreat from negative emotion. They don’t try to rescue people from it and make them feel good. Rather, they use it for its developmental potential. The psychologist Roberto Assagioli has said, “a psychological truth is that trying to eliminate pain merely strengthens its hold. It is better to uncover its meaning, include it as an essential part of our purpose and embrace its potential to serve us.” When leaders try to reassure people or make the pain go away, they rob it of its power. It is better to acknowledge the pain and embrace it so that it can be used to fuel growth.“As painful as it feels now, it will help him.”So, what does ‘leaning in’ look like? Consider “the shot.” Kawhi Leonard’s quadruple bouncing Game 7 buzzer beater was a moment of euphoria for Toronto. On the other side, however, it was a devastating moment for a young Philadelphia 76ers team featuring 25-year-old star Joel Embiid, who left the court in tears. When asked about the emotional response of Embiid in the post-game press conference, Philadelphia head coach Brett Brown said, “As painful as it feels now, it will help him. It will help shape his career.” Rather than shying away from the pain, comforting Embiid and trying to lessen the sting, Brown leaned into it and helped his young player see it as a growth opportunity – a sign that he needed to work harder. 2. Frame negative emotion differently Leaders of resilient teams have a different answer to the question “what is this pain telling us?” than leaders of less resilient teams. They frame pain as a signal that they aren’t there yet – rather than a sign that they aren’t good enough. As a result of this framing, resilient teams respond to negative emotion with determination. They get committed to the challenges they face by exerting control where it matters: their own effort. After a lacklustre season heading into Salt Lake City in 2002, the Canadian women’s hockey team held a player’s only meeting where they came up with the acronym WAR, for ‘We Are Responsible.’ As 4-time gold medalist Janya Hefford reports, “there was a lot of the blame game going on”– and the WAR framing helped them redirect attention away from the officiating, their opponents, etc. and towards what they were responsible for. Ultimately, this perspective proved vital in overcoming 8 straight penalties in the Gold-Medal game to triumph. 3. Channel negative emotion After embracing negative emotion and finding its meaning, teams and their leaders must still channel the emotion into positive outcomes. Our founder, Peter Jensen, will often ask teams who have suffered failure one powerful question: “What are we going to do with the energy under this emotion?” it’s easy to channel emotion into what Ben Zander has called “the conversation of no possibilities” and allow the dangerous side of negative emotion affect to take over. Channeling negative emotion productively requires individuals on teams to take responsibility for redirecting energy towards growth and hard work.