At Third Factor, we’ve spent over four decades working at the intersection of business and sport. Our programs have always been shaped by the high-performance principles used by Olympic coaches, elite athletes, and championship teams. Today, we’re proud to deepen that connection with the formation of our Sport Advisory Board—a small, purpose-driven group of leaders who are shaping the future of sport.

The Sport Advisory Board is an extension of our deep involvement in sport, and our philosophy that we find the best ideas by cross-pollinating ideas across different domains. It will help ensure that our offerings in the corporate world stay grounded in the latest insights from high-performance environments. Just as importantly, it provides a space for these sport leaders to access our coaching, consulting, and facilitation services to support their work developing athletes, teams, and organizations.

We’re honoured to introduce the inaugural members of the Third Factor Sport Advisory Board:

Mel Davidson

Mel Davidson is a legend in women’s hockey, having led Team Canada to Olympic gold as head coach in 2006 and 2010 and as general manager in 2014. Across 36 international events, every team she’s led has reached the podium—a testament to her leadership and consistency under pressure. Today, Mel is a high-performance advisor with Own the Podium, supporting national team programs across Canada. Her expertise in team dynamics and coaching strategy, along with her no-nonsense approach to performance, is a major asset to the board.

Debbie Low

Debbie Low is President and CEO of the Canadian Sport Institute Ontario (CSIO), where she has transformed the organization into a national leader in athlete development. Her background spans leadership roles across parasport and major games, including serving as Chef de Mission at the 2008 Paralympics. Recognized for her impact on sport and inclusion, Debbie brings a strategic lens and deep systems knowledge to our advisory conversations.

Jesse Lumsden

Jesse Lumsden is a dual-sport athlete and rising leader in Canadian high-performance sport. After a successful CFL career as an all-star running back, Jesse transitioned to bobsleigh, representing Canada in three Olympic Games and earning World Championship medals. Today, he serves as High Performance Director for Bobsleigh Canada Skeleton. Jesse brings firsthand experience of high-stakes competition and athlete transition—along with a deep commitment to developing performance cultures that last.

Tracy Wilson

Tracy Wilson is an Olympic bronze medalist, broadcaster, and one of Canada’s most respected figure skating coaches. Alongside her late partner Rob McCall, she won seven consecutive national titles and the pair made history as the first Canadian ice dancers to reach the Olympic podium. Today, Tracy is a leading coach alongside Brian Orser at the Toronto Cricket Skating and Curling Club, working with Olympians like Yuzuru Hanyu and Javier Fernández. Her blend of technical mastery and focus on mindset makes her a powerful contributor to our advisory board.

We’re grateful to Tracy, Mel, Debbie, and Jesse for lending us their expertise. Through this board, we’ll continue to strengthen the bridge between sport and business—ensuring that the lessons learned on the field, ice, track and training room find meaningful application in boardrooms and organizations everywhere. Over the past year I have worked with hundreds of leaders across a range of industries. And the most common question they have asked is “How do I sustain the energy levels of my people?”.

This year, more than any other in recent memory, has taxed the energy reserves of even the most resilient teams. Hugely disruptive changes, prolonged periods of uncertainty and the blurring of work and home have drained people’s batteries and made it difficult to recharge.

When leaders try to step in and fill the energy gap, it’s not long before they find themselves starting to run out of gas. The key is to take on the challenge, without trying to do it all on your own.

A team’s energy comes from within

A while back I was leading a Self-Aware Team program for the coaches and support staff of a team that was preparing to represent Canada at the Winter Games in Beijing. An important part the program is an exercise in which team members create “player cards” containing key insights they’ve learned about themselves through the program. The group then comes together in a Zoom call to share those insights and give and get feedback.

Like so many others, this group had been through an incredibly taxing year. Because of the pandemic, the team had to expend significantly more energy than it ordinarily would to create effective training opportunities for the athletes. Quarantines and “bubbling” rules had forced individuals to spend months at a time on the road, adapting to new routines and away from their families. And uncertainty over everything from health and testing to the potential fate of the games loomed over it all.

“The ways they brought energy were as diverse as the people themselves.”

As the group shared their player cards, it quickly came to light that a number of different members of this team had been significant “energy givers” through this difficult time. And the ways they brought energy were as diverse as the people themselves.

- One senior leader on the team created energy in the more traditional way that many leaders do: by envisioning a compelling opportunity, mapping out a plan to get there and leading the charge towards it.

- Another team member helped bring lightness to the daily grind by noticing and pointing out funny moments, breathtaking views, or interesting aspects of their surroundings. These moments created mini-breaks that relieved tension and reminded the team of the unique and special journey they were on together.

- Another contributor was celebrated for their “can-do attitude.” This individual had a “big personality” with a healthy dose of confidence who led by example and encouragement. Their jokes, positive energy and infectious smile helped the team forge ahead with a belief that they could prevail when they were hit with a setback or success seemed a long way off.

- Yet another had taken on the role of a confidante and created a safe, non-judgmental space for people to bounce ideas, vent frustrations and seek advice when they needed to gain perspective on a situation (or person) that was creating challenges.

Three energizing principles

In listening to the group share their feedback, I was struck by three things:

Energy is found in diversity. During the discussion I heard multiple different ways that multiple different people infused the group with energy. Some provided big boosts, other provided steady nudges. Some energized all team members. Others were more critical in sustaining a handful of specific individuals. Some were helpful at the start to get the flywheel moving forward. Others stepped in during negative moments to break tension and redirect focus when forward movement was stalled. Each team member’s contribution could stand on its own, but put together they added up to more than the sum of their parts.

Energizing the team is everyone’s responsibility. No single contributor can create enough energy on their own to sustain a team; the demands are simply too vast. Everyone on the team shares some responsibility for energizing their teammates. The team leader’s job is to create the conditions that allow it to happen.

Feedback is of key importance. In many cases, the “energy givers” were surprised to learn the value of what they provided. In fact, some had mistakenly believed that the very behaviors that others found energizing were irrelevant or a distraction. If not for the reinforcement they received during the session, many had been planning to curtail some of those behaviors moving forward. And, if that had taken place, then valuable sources of positive energy would have simply faded away because people were unaware.

Energize your team

Every leader needs to create an environment that enables their people to perform. And energy is a critical part of that environment. But it’s not the leader’s role to provide that energy all on their own. Instead, the best leaders create the conditions for “energy givers” to thrive.

“Create a clear image of what it looks like to be an energy giver.”

Start by setting the expectation that energy is a team responsibility. Work with your people to create a clear image of what it looks like to be an “energy giver” and what behaviors will move the team’s energy level in a positive direction.

Help your team surface the different ways “energy givers” sustain the team in tough moments. Make it a part of your regular check-ins to ask people what’s contributed to their energy over the past week and encourage open discussion when appropriate.

Finally, provide opportunities for regular feedback and recognition so that each “energy giver” knows what to keep doing. This feedback can come from you as a leader, but people should also hear from their peers. Effective feedback recognizes the behavior, communicates its impact, and encourages the person to continue.

With this approach, a leader can create more energy on their team than they could ever hope to do alone, while at the same time helping their people to stay engaged and motivated through whatever may come. Editor’s note: This article was first published on April 14th, 2020, just a few weeks into the COVID-19 pandemic. While the context may have changed, your plays as a leader are still the same.

In this article:

Four imperatives for leaders in times of uncertainty

In these uncertain times, you are likely facing new challenges as a leader.

From working from home to school closures and outright community lockdowns – everyone has been dealing with significant, unexpected change over the past few weeks. These changes have impacted us all – changing the way we communicate, work together, and accomplish our goals.

During these tough times what we have noticed is people’s desire to help others. The feeling that we will come through this together is a rallying cry that gives heart to many. But as leaders, as coaches, what does this mean? How do you help your people during times like this? It’s a question many are struggling with.

It’s all about the relationship

When people go through difficult times together, they can emerge more connected – but only if they’re conscious about it. Difficult times can also lead to fracture. As a leader, it’s your job to step back and really think about how you are building and deepening relationships with your people in this new environment.

Take the time to check in with your people and listen to them. Take some time to step back and see what you’re going through as impartial observers and acknowledge that it’s hard. These are unprecedented times and the effort you make to stay connected with your people can make a huge difference.

Coach Roy Rana of the Sacramento Kings spoke with us about how building relationships is intentional. There is an intention to communicate, to make the person feel connected, to ensure they know they have your attention. He talks about the little things that he does to accomplish this. In the video below, he lays out the wonderful challenge he sets for himself of “30 seconds every day for every player”:

Rana’s Strategies are for basketball – not your environment. So what would work for you? What are the little ways you can connect with your people to communicate that you are thinking of them and you care?

The game has changed

By now, every workplace has been impacted by COVID-19. The game has changed, and clarity needs to be re-established. Your team needs new skills and mindsets so that you can get through this together.

“We can’t go back, only forward.”

Ask yourself what your team needs for their new playbook. Do your people know what the work expectations are today? Timelines are different. Things change quickly so clarity is always evolving. Think short term and help them find focus. Do they know what other people need from them? Are they aware of how your goals have shifted? Especially if your team is working differently than they’re used to, over-communication is impossible when it comes to these things.

Your team also needs clarity on what your organization’s values look like in this reality. Not just the vague, nice-sounding words – what they actually look like. If you value safety, how are you acting on that value? If you value team, how are you making sure that no one’s feeling isolated? Get together as a team to discuss your values and think through how you’re living up to them at this time.

Through all of this, recognize that as a coach you need to meet your people where they’re at. Some team members might be juggling kids and other family constraints. They may even be caring for someone who is sick. Give them real clarity on how your team can work well together in a way that’s not going to make anyone feel criticized, judged or guilty. Have empathy for what they’re going through and use humour to help people feel at ease.

Some team members (and perhaps even you) may be thinking they just need to hold on for a little bit longer until things get back to normal. That thinking will not serve them or the organization well. When companies face disruption, the ones who try to ignore it or find a way to hang on to their old ways of doing things don’t fare well – think Blockbuster. We can’t go back, only forward.

New plays for a new game

When the game changes, you can’t expect to get the same results from the same behaviours. As a coach, your goal is to help your people succeed in their new reality – and this means helping them get up to speed on the skills that will support the new expectations as well as discouraging the old behaviours that are no longer productive.

This is all about consistent feedback and communication, and feedback is a challenge when you can’t see what people are doing. For the coachee, the lack of visibility can lead to frustration and unnecessary roadblocks that can harm engagement. Make a habit of checking in frequently with each team member to support their development. This isn’t about micromanaging or checking up on them; it’s about making sure they’re not sitting alone frustrated because something’s blocking their progress.

If that sounds like a big job, that’s because it is. Coach Rana told us about how making time for each and every team member is a challenge even as a professional coach. And he offered this advice for keeping the connection alive even when it feels like you’re too busy.

Out of sight, not out of mind

If what I’m doing can’t be seen, how do I know if it’s valued or appreciated?

This is one of the challenges your people are facing as they transition to a new reality. People need to know that what they do has value, so giving appropriate recognition is more important now than ever.

This doesn’t mean handing out awards and prizes. It’s about looking for the bright spots – things that are going well, little wins, positive behaviours – and acknowledging them. You might recognize a team member who creates a shared space for everyone to connect, or someone who volunteers to take on a task for another team member they see struggling.

It’s also vital to recognize that people need to feel connected and not isolated. Make every conversation a coaching one. Even simple questions like “how are things going today” have value for a coach. As you explore the answer, you can uncover the information you need to find possibilities and build commitment to a solution. When people are worried, anxious or afraid they’re harder on themselves than ever. Having the coach remind them of who they are at their best brings tremendous energy.

Be ready for the human element

Behind all this is a real humanitarian challenge. As time goes on, the people on your team may become sick, need time off to care for loved ones, or worse. Loss is going to look very different for different people – it can be loss of a loved one, income, or something else. As a coach you have a role to play in supporting your team members as they recover from whatever their loss may be.

The temptation is to think that when someone is in pain over their loss that bringing it up will cause undue pain by reminding them of it. Just keep to your work and ignore it. And that’s like the monster under the bed for a little kid. As long as the kid believes there’s a monster under the bed it gets bigger and bigger. The longer it goes, the bigger it gets.

“When loss isn’t acknowledged, it feels like it’s been dismissed.”

This is true on both sides of the relationship. In Sheryl Sandberg’s book, Option B: Facing Adversity, Building Resilience, and Finding Joy, she talks about how the hardest part of going back to work after losing her husband was the silence. When loss isn’t acknowledged, it feels like it’s been dismissed. And a significant loss being dismissed feels really bad.

You don’t need to be a counsellor or have all the answers, and there’s no secret formula for how to deal with these times. Your job as a coach is to bring things to the surface and give people permission to talk about it if and when they want.

Help people get better at whatever it is they do

We often define a coach’s core job as this: help people get better at whatever it is they do. We call this developmental bias, the idea that a coach is always biased toward developing their people no matter what the circumstance. As the “whatever it is they do” continues to change and evolve over the coming months, and probably years, you have an opportunity to help your people stay engaged and rise to the occasion.

By maintaining and building relationships, building clarity around what’s expected, building competence in new ways of working, and recognizing the all of what is happening, you can show your people that you’re on their side and help your entire team emerge stronger for it. In 2002, the Canadian Women’s National Hockey Team entered the Olympic Games in Salt Lake City in an unfamiliar position: as underdogs. They had not hit their stride as a team, their confidence had taken a hit, and emotions were at risk of boiling over. In eight head-to-head games against the Americans leading up to the Olympics, Canada had lost all eight. For many players, it was hard to avoid memories from four years earlier when the team had lost to the Americans in the gold medal game.

Jayna Hefford, who was playing in the first Games of her Hall of Fame career, recalls the point when the stress and emotion came to a head: “There was an intense conversation in the dressing room with the team. A lot of people had a lot to say about things we needed to do and how we were going to get better, and we realized that a lot of what was happening was the blame game.”

“We realized that a lot of what was happening was the blame game.”

Through a frank, players-only discussion the team was able to come together, but the conversation could have gone a number of different ways. It stayed on track because the team was prepared – mentally and emotionally – to have performance conversations under pressure and surface a number of issues the team needed to resolve. And that preparation turned out to be an important stepping stone to winning gold in Salt Lake City.

Training the bomb squad

Handled poorly, team communication under pressure can lead to combustion. And just like you wouldn’t get success as a bomb disposal technician going in without their toolkit, you won’t find success in communicating through tense situations if your team isn’t prepared. The advantage the women’s team had that allowed them to emerge from that conversation united was a deep awareness of their communication tendencies and systems to counteract the counterproductive ones. They had laid the foundation for performance conversations in good times so that they could happen and be productive when the difficulty hit.

In other words: they had a tool kit and they knew how to use it.

“The biggest opportunity for meaningful growth is often to increase self-awareness and strengthen their ability to communicate productively when under pressure.”

We’ve worked with hundreds of teams in elite sport and business, including the last four medal-winning Canadian women’s hockey teams. One of the things we’ve learned is that when teams are already operating at a high level, the biggest opportunity for meaningful growth is often to increase their self-awareness and strengthen their ability to communicate productively when under pressure. To support this, we’ve developed a process to help teams become more aware of their tendencies, develop systems and practice performance conversations anytime.

At the heart of this process is a tool called the TAIS – The Attentional and Interpersonal Styles inventory. The TAIS was developed for use by Navy SEALs and Olympic athletes, and we’ve found it to be an incredibly valuable tool for diagnosing communication challenges on all kinds of teams. When the pressure is on, when teams are in the midst of setbacks and failure, individuals will fall back on their default communication styles.

Five communication choices

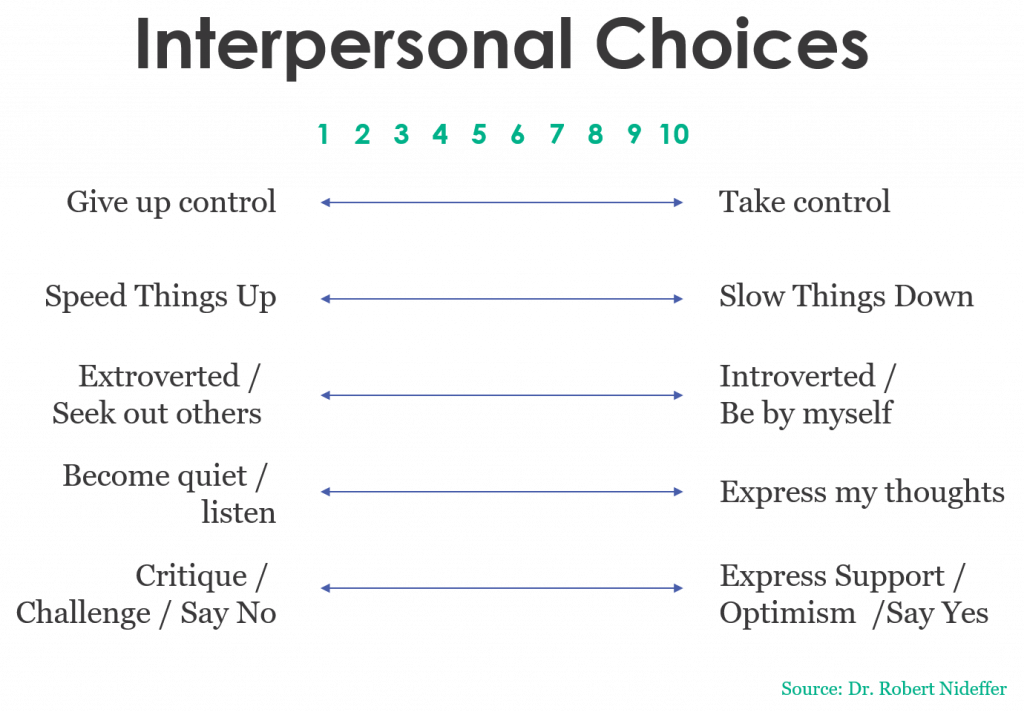

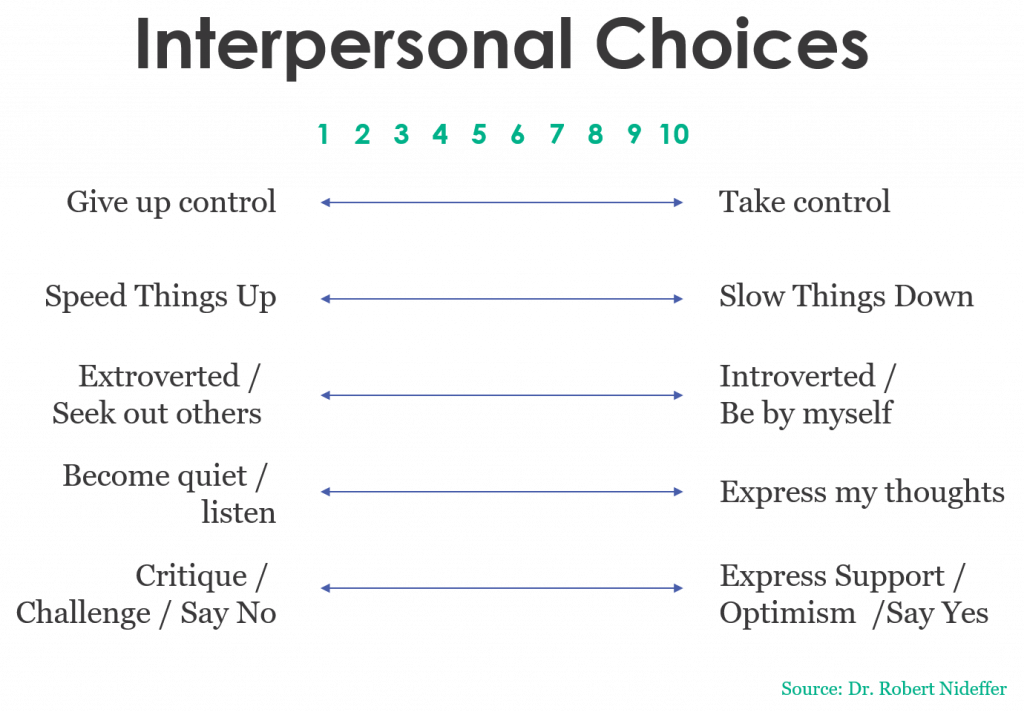

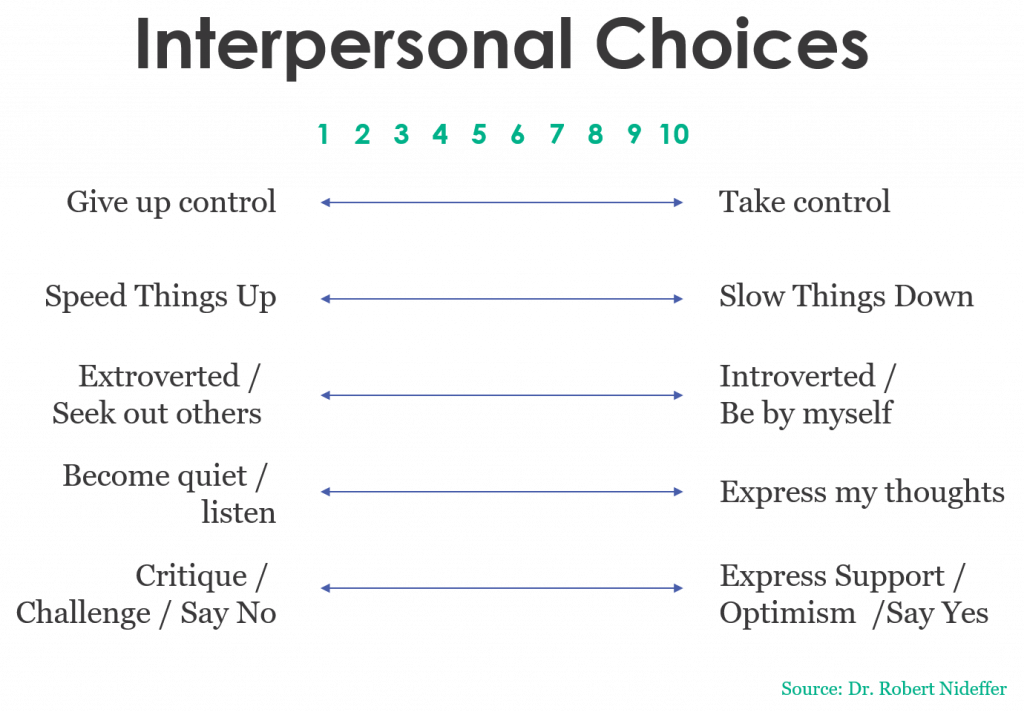

The author of the TAIS, Dr. Robert Nidefer, showed that people make five choices over and over in the course of a conversation. These choices are informed by their tendencies on five dimensions.

Give up/take control – are you more likely to try to take control, or cede control to someone else?

Speed up/slow down – are you more likely to force action or a decision, or encourage more thought and consideration?

Extroverted/introverted – are you going to seek out others, or try to solve the problem yourself?

Become quiet/express thoughts – are you going to become quiet and try to understand, or advocate for your position?

Critique/express support – will you say no and become more critical, or will you say yes and express support?

Cut the right wire

Every team will have members with different tendencies. Ultimately, it’s not the tendencies that matter; it’s the level of awareness team members have of their tendencies, and the systems they put in place to leverage their strengths and weaknesses in the heat of the moment. The highest performing teams we work with take three critical steps in preparing for productive communication under any circumstances.

Acknowledge the “I” in team

Great coaches know that the phrase “there is no I in team” is a myth. Every individual makes their own contribution – and without self-awareness, people can’t adjust. That’s why the first step in your team’s communication action plan is to encourage every individual to build self-awareness across these five choices. By knowing and understanding their default tendencies, team members can begin to recognize their behaviour and course-correct when necessary for the good of the team.

Connect to the “we” of the team

It’s advantageous to know your individual tendencies, and the value is multiplied when that information is shared with everyone on the team. When you raise the waterline of team awareness, everyone can work on the same communication system. Team members can see the intent behind the behaviors their teammates exhibit. The process can be incredibly difficult; Team Canada Captain Hayley Wickenheiser called sharing her profile with her team-mates, “the most stressful part of the 4-year [Olympic] quadrennial.”

Come together as a team

Armed with knowledge of self and others, teams can come together and translate self-awareness into action. When pressure hits, if everybody on the team has the tendency to get louder, express their thoughts and try to take control of the conversation, the team can make decisions in advance to decide who’s going to take control when issues arise. By having these conversations earlier, teams can build systems to fall back on when the pressure is turned up.

Preventing detonation

The next time you’re headed into a potentially high stakes conversations, use the five choices below to carry out a short 3-step preparation exercise:

1. Plot your default tendency on each of the five scales – given your past history, where are you most likely to fall?

2. Where would you ideally like to be as you head into this specific interaction?

3. What are the gaps between your ideal and default style? What actions will you take to ensure you are at your ideal?

Repurpose the fuel for growth

We’ve said before that negative emotion is volatile fuel. Improperly handled, it can lead to combustion. Used properly, it can lead to high performance.

Team communication must go beyond just staying cool during difficult times. Teams must use communication to understand and lean in to their negative emotions, uncover what the emotions are telling them, and frame it as an opportunity for growth. This is what happened with the women’s team in 2002. They prepared to have productive communication at all times, and used the tools they learned to find the opportunity for growth at a moment when it could have blown up. Jayna Hefford explains:

By understanding your individual communication style, sharing your tendencies with the team and proactively planning to address potential faults, your team can find its way through difficult times and not just safely diffuse difficult situations but find new strength and opportunity for higher performance in the process. When the trajectory of your life hangs in the balance of one critical moment – when your heart is racing, your palms are sweaty, and your breathing is ragged – how do you nail it?

Few people are better qualified to answer this question than Olympic skating legends Brian Orser and Tracy Wilson. As athletes, they carried the weight of a nation at the 1988 Olympic Games in Calgary – entering as a reigning world champion and 7-time Canadian champion, respectively. Competing in front of a home crowd with incredibly high expectations, Brian and Tracy won 2 of Canada’s 5 medals in Calgary.

Today, Brian and Tracy are coaches to a new generation of elite skaters from around the world at the Toronto Cricket Club. They’ve produced gold medalists for the last 3 Olympic games and currently coach the reigning Olympic men’s champion, Yuzuru Hanyu of Japan, and the reigning Olympic women’s silver medalist, Evgenia Medvedeva of Russia.

As athletes and coaches, Brian and Tracy have delivered exceptional performances in moments of intense pressure. In this video series, they shine some light on their experience performing under pressure and coaching athletes to perform under pressure, and reveal simple strategies you can use to be at your best in your own most critical moments.

“There was a media frenzy”

Brian Orser describes the media frenzy and inescapable layers of pressure he felt leading up to the ‘Battle of the Brians’ on home ice at the 1988 Calgary Olympics.

“What got me so excited was representing Canada”

Tracy Wilson shares how she practiced the emotional moments in advance of competition at the 1988 Olympic Games in Calgary.

“We were prepared for any scenario”

Brian Orser talks about how he established and practiced routines for any situation, whether he had to skate first or wait around to skate 6th.

“I hate this part”

Tracy Wilson explains how leaning into emotions can help performers diffuse tension and how coaches can use communication to help their team members perform at critical moments.

By Dane Jensen / CEO, Third Factor

All teams suffer setbacks. What separates resilient teams from the rest is how they respond. Resilient teams come back stronger after failure because leaders and team members lean into the negative emotions that inevitably accompany setbacks and use the energy under those emotions to fuel recovery.

Negative emotion is volatile fuel

Heading into the women’s World Cup in 2011, Canada’s national soccer team was one of the favourites. Two weeks later, they were knocked out of the round robin in a 4-0 defeat to France and headed home without winning a game – finishing dead last.

“It wasn’t going to define us”

Team Captain Christine Sinclair talked about feeling “humiliated” – like they had let down the country. And yet just one year later, the same team outperformed at the London Olympics to win Canada’s first ever medal in soccer. “We knew what we were capable of and just because we had one bad tournament it wasn’t going to define us,” said Sinclair. The head coach of the Women’s National Team, John Herdman, spoke about how the team was “an easy group to motivate” because they had just suffered such a crushing defeat.

Negative emotion can be powerful fuel for positive response. It can provide ‘bulletin board material’ that leads to determination, and ultimately harder work and higher standards.

But negative emotion is highly volatile fuel. If not handled correctly, it can trigger a negative feedback loop that leads to the blame game and teams that end up either combusting or just detaching.

Three Jobs for Leaders of Resilient Teams

We’ve observed that leaders of resilient teams are able to trigger the positive feedback loop from negative feedback by doing three things differently than leaders of less resilient teams:

1. Lean into negative emotion

Leaders of resilient teams don’t retreat from negative emotion. They don’t try to rescue people from it and make them feel good. Rather, they use it for its developmental potential.

The psychologist Roberto Assagioli has said, “a psychological truth is that trying to eliminate pain merely strengthens its hold. It is better to uncover its meaning, include it as an essential part of our purpose and embrace its potential to serve us.”

When leaders try to reassure people or make the pain go away, they rob it of its power. It is better to acknowledge the pain and embrace it so that it can be used to fuel growth.

“As painful as it feels now, it will help him.”

So, what does ‘leaning in’ look like? Consider “the shot.” Kawhi Leonard’s quadruple bouncing Game 7 buzzer beater was a moment of euphoria for Toronto. On the other side, however, it was a devastating moment for a young Philadelphia 76ers team featuring 25-year-old star Joel Embiid, who left the court in tears. When asked about the emotional response of Embiid in the post-game press conference, Philadelphia head coach Brett Brown said, “As painful as it feels now, it will help him. It will help shape his career.” Rather than shying away from the pain, comforting Embiid and trying to lessen the sting, Brown leaned into it and helped his young player see it as a growth opportunity – a sign that he needed to work harder.

2. Frame negative emotion differently

Leaders of resilient teams have a different answer to the question “what is this pain telling us?” than leaders of less resilient teams.

They frame pain as a signal that they aren’t there yet – rather than a sign that they aren’t good enough. As a result of this framing, resilient teams respond to negative emotion with determination. They get committed to the challenges they face by exerting control where it matters: their own effort.

After a lacklustre season heading into Salt Lake City in 2002, the Canadian women’s hockey team held a player’s only meeting where they came up with the acronym WAR, for ‘We Are Responsible.’ As 4-time gold medalist Janya Hefford reports, “there was a lot of the blame game going on”– and the WAR framing helped them redirect attention away from the officiating, their opponents, etc. and towards what they were responsible for. Ultimately, this perspective proved vital in overcoming 8 straight penalties in the Gold-Medal game to triumph.

3. Channel negative emotion

After embracing negative emotion and finding its meaning, teams and their leaders must still channel the emotion into positive outcomes. Our founder, Peter Jensen, will often ask teams who have suffered failure one powerful question: “What are we going to do with the energy under this emotion?”

it’s easy to channel emotion into what Ben Zander has called “the conversation of no possibilities” and allow the dangerous side of negative emotion affect to take over. Channeling negative emotion productively requires individuals on teams to take responsibility for redirecting energy towards growth and hard work.

Negative emotion is fuel for growth

Resilient teams process negative emotion in a way that leads to harder work and higher standards as opposed to detachment or combustion. They do that by leaning into negative emotion rather than retreating, by framing it a little differently and by seeing it with a sense of challenge, control and commitment.

As a leader, your job is to create the conditions that allow negative emotion to be used to its full potential. The next time your team suffers a setback, encourage your team to accept their feelings, find meaning in their failure, and channel their emotions to come back stronger than before. On November 19th, 2019, 75 leaders from Toronto’s business and HR communities gathered at OCAD U CO for a discussion on team resilience. Here’s what they learned:

Leading the discussion, Third Factor CEO Dane Jensen brought together the voices of elite athletes and coaches to talk about what separates those teams that are able to rebound from failure to reach even higher levels of performance from teams that tend to crumble or falter in the face of failure.

Drawing on insights from our work with high-performing sports teams, including the last four medal winning women’s Olympic hockey teams and the men’s and women’s national soccer teams, Dane identified what it takes for teams to not just perform but also to recover and be resilient. These are the four traits we’ve observed that characterize resilient teams, or differentiate resilient teams from those that are less resilient:

1. Negative emotion. Resilient teams process negative emotion in a way that leads to harder work and higher standards as opposed to detachment or combustion. They frame it so rather than being scared of negative emotion, they choose to lean into it, work with it, and see it with a sense of challenge, control and commitment.

2. Communication. The teams that recover quickly from setbacks communicate differently because they have worked consciously on awareness. They’ve surfaced their communication styles and worked on having performance conversations in the good times.

3. Relationships. Teams are more resilient when they work diligently on building relationships, even if that’s just 30 seconds for each person every day.

4. Shared purpose. Teams work best in the face of failure when they have a clear a line of sight to shared purpose. They don’t do hard work for it’s own sake, but because they choose to connect it to something that actually matters to them.

JOIN US FOR OUR NEXT LEARNING BREAKFAST

Be the first to know about upcoming learning opportunities from Third Factor by entering your information below.

“I was covering a colleague’s position while she was on maternity leave. She has now returned and we have negotiated shared authority and management roles. Co-management is not easy. Now we have to see where our roles intersect and what makes us distinct. It was so much easier to be the sole operator and know exactly what my role was and what I was accountable for. I think that is the hardest part. How do we decide about accountability?”

In our workshops, we constantly talk about the importance of clarity. Nowhere is this more important than in areas of joint responsibility. My preferred starting point for clarity in these situations is the basic building block of management responsibility: the decision.

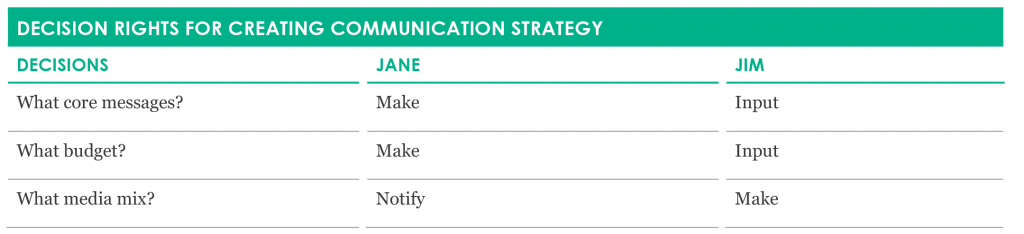

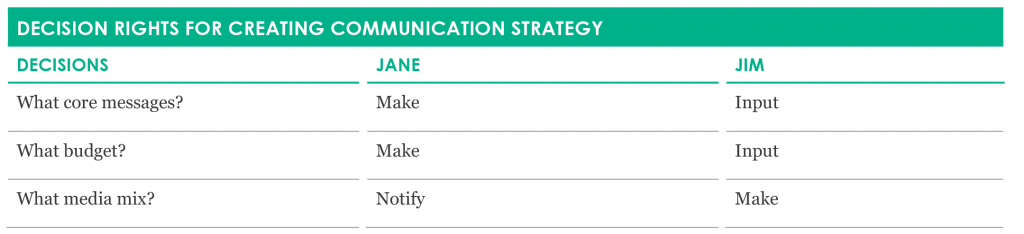

First and foremost, you and your colleague must be on exactly the same page with respect to what the key decisions are that are made in the course of your work, and then you need to have an open and frank discussion around who has the right to ‘make’ the decision vs. who has an ‘input’ right (I.e. They need to be consulted, but ultimately the decision is not theirs to make), or even just a ‘notify’ right (I.e. They must be notified once the decision has been made).

A lot of the issues in shared roles come when people believe they have a make right, but actually they just have an input right, or vice versa. Agreeing on this up front can diffuse a lot of potential tension.

It is very tempting to establish ‘joint make’ rights for key decisions—i.e. we both need to agree to make the decision. In my experience, ‘joint make’ rights cause some significant issues in the real world, and often lead to paralysis. Even though it can be very painful up front, it is better to align on one person who ultimately has the responsibility for making each decision. These ‘make’ rights would ideally be aligned with the unique knowledge, skills, etc. that you bring to the table. Sometimes this may not be possible, but try to use a “joint make” very sparingly.

One way to think about making this real is in going through the core job responsibilities you’ve outlined in your job description and really honing in on what the choices implied in each. For example, let’s say one element of your job is to “oversee the creation and implementation of a comprehensive communication strategy”. Within this task you might have 3 key decisions: 1) what core messages are we highlighting to which audiences, 2) what budget are we allocating for communications, 3) what media mix are we going to use. What you want to do is isolate the decisions that are likely to be hotly contested, and make sure you have clearly laid out decision rights with your partner. For example:

Once decision rights are clarified, accountability is easy: you are accountable to your supervisor for the decisions over which you have a ‘make’ right, and your accountability as colleagues is that you will effectively provide for, and really listen to, input across all decisions where you have agreed that the other person has input rights. Allocating decision rights is an exercise in power. Prepare for the discussion with your colleague to be a challenging one. If you push through it, however, you will have a solid foundation upon which to build a productive, collaborative relationship.

Click here to download this article as a PDF.